JUN IGARASHI

PEOPLEText: Hanae Kawai

Jun Igarashi, influenced by his grandfather’s work, went on to become not only a mere architectural planner but a highly sought-after designer and lecturer in Japan and overseas, especially in Scandinavia and continental Europe. ‘I want to discover a “benign virus” that will transform Sapporo and Hokkaido into places brimming over with excitement,’ he says. He’s had a hand in planning our own MUSEUM and the exhibition of architectural sketches ‘Homage to Arne Jacobsen,’ hosted by Fritz Hansen. During our interview, he spoke about these projects as well as discussing the scenery of words and concepts that inform his practice, which shed us some light into his way of thinking. In September, he will give lectures taking place during Helsinki Design Week in Finland. We also asked him about relocating his work to Sapporo.

Jun Igarashi

First of all, please introduce yourself and your work to our readers.

I’m an architect, and I run Jun Igarashi Architectural Office.

“Rectangular Forest” Jun Igarashi, 2000, Photo: Shinkenchiku-sha

As someone who is active in Japan and abroad, tell us about how you first became involved with the field of architecture and the appeal it has to you.

He had been a builder in the army, constructing bridges and other facilities in the battlefront. I also heard that he used to make wooden sleds. My dad kept our construction business going and now I’m the third generation to be involved in it. Since I was little, I grew up around grandfather’s work and was definitely influenced by it. Though it’s a bit unclear to me as to how exactly it happened, that was the road that took me to the field of architecture.

“wind circle” Jun Igarashi, 2003, Photo: Shinkenchiku-sha

With technological advances, we could say that contemporary architecture is becoming more complex and complicated. On the other hand, looking at your work we feel a sense of simplicity in colours and shapes. During the planning stages, what goes on in your mind in terms of, for example, architectural themes?

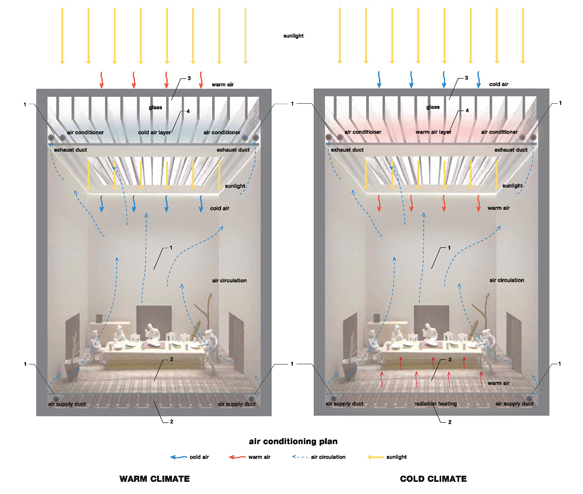

Architecture and technology have always walked hand in hand, and that will remain the same in future I think. Complex architecture stems from advances in technology, especially in large scale architectural projects, which employ a number of advanced construction techniques. Buildings constructed with these advanced techniques often stand out to the public eye, which leaves an impression that architecture is becoming more complex. But in the history of human kind, architecture goes back to the dawn of civilisation so I think that my practice has evolved as a response to the very basic elements of existence. Especially light and wind, comfort, taking pleasure in simplicity are things I always consider in my work.

“Korogaru Park in Nature” YCAM InterLab+Jun Igarashi, Sapporo, 2014, Photo: Jun Igarashi

With sunlight shining through the trees and children’s voices echoing all around, the Korogaru Park in Nature, a collaboration between you and YCAM InterLab, was such a wonderful place that I wished it was a permanent installation. What were your thoughts developing it?

It was a project that happened by chance. Originally, YCAM InterLab had the original concept all planned out, so at the beginning for me it was a pretty tough job. While simply coming up with ideas for the project, I thought that an orthodox playground was out of the question. When children play in nature, with the sheer power of their imagination, they discover novel ways to play with things they take from the environment, like in a forest for example. A playground is a more systematised way of telling children how and where to play, while I was thinking of something along the lines of letting children discover how they want to play. In other words, starting from the point of view of a child exploring their environment, I wanted to build a space that would undergo numerous changes the more you played in it. Less of an amusement park, more like a simulation of a forest.

“Wind circle” Jun Igarashi, 2003, Photo: Shinkenchiku-sha

Out of all the projects you’ve been involved with, which one is the most memorable to you?

Naturally, I strive for the best outcome in each project I’m involved with, so they have all been very memorable to me. There’s a line of thought, a sense of continuity in each design I make so every project is dear to me. Though merely only a few of those designs will eventuate into real projects.

‘Rectangular Forest‘ was my debut project, and the ideas I developed there became the base for all my subsequent work.

In ‘Ring of Wind,’ I discovered that by embracing the geography and climate peculiar to Hokkaido in my work, it would allow me to acquire a new sensibility in architectural terms. ‘Rectangle of Light,’ ‘House of Trough,’ ‘The Gap in the Gate,’ were all logical conclusions and a natural expansion of the concepts I had developed up that point. Finally, in ‘Ordos 100,’ which I developed in the Inner Mongolia region, I managed to capture and convey a sense of distance felt in that environment.

“Rectangle of Light” Jun Igarashi, 2007, Photo: Jun Igarashi

“House of Trough” Jun Igarashi, 2008, Photo: Jun Igarashi

Your work is highly regarded in Japan and abroad. Did you set out from the beginning to pursue such recognition overseas?

I had no idea my work would have followers overseas. However, when I began my architectural practice in 1997, not long after the release of Windows 95, just at the dawn of the Internet age. My gut feeling is that if you aspire to produce good architecture then it will get noticed by people, wherever they are from in the world.

“Homenaje A Arne Jacobsen”, Flitz Hansen, Jun Igarashi, 2015

As a part of the ‘Homage to Arne Jacobsen‘ exhibition this past July, you were one of the designer/architects selected by household name Fritz Hansen to reimagine the classic ‘Series 7’ chair, originally designed by Jacobsen, as a part of the 60th anniversary exhibition of that design. Tell us how you came up with your own take on such a timeless piece.

I always get many sudden project requests by mail, and this project was no different. Zaha Hadid and Jean Nouvel were already involved with it at that point, while all the other participants were representing their own countries. So I was excited to represent Japan in such an international pool of talented people, and also the Series 7 chair is one of my favourite designs. I was really glad to receive such an offer. I felt tremendous pressure to create something original while being respectful to the classic lines of the Series 7.

“Layered House” Jun Igarashi, 2008, Photo: Jun Igarashi

In your recreation of the chair, you seem to have used recycled construction materials. How did you come up with this approach and how did your creation process evolve until its completion?

I didn’t set out to simply create a new design, my idea was to take on board the context surrounding the Series 7 chair. As an industrial design, it was meant for mass consumption. I think that’s the same approach I use in my architectural practice. Again, the act of manufacturing is another very primal human activity, possibly something that started in the Stone Age. That means I wasn’t trying to criticise industrial manufacturing as a whole, but just looking at it in another way. As in there must be something in between manufacturing and recycling that we could all explore and move forward. The concrete debris scattered all over after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake left a deep impression on me. Then I thought, in Japan why couldn’t we start to make buildings with wood again, though they have a short lifespan but are easily recyclable. That way we somehow could at least reuse the timber scraps from old buildings in mass manufacturing once again.

“MUSEUM” Jun Igarashi, Sapporo, 2014, Photo: Jun Igarashi

On the topic of revitalising an older building, our own Shift editorial office inside the MUSEUM went through a very Hokkaido-esque type of renovation. Unusual for such a job, qualified tradesmen were not involved so the Shift staff had to get their hands dirty and help with the renovation themselves. How was that experience for you?

My first impression was that the building skeleton frame was superbly built. As we started to remove the thick outer layers from the walls, we came up with our own ‘building regulations’ and started the renovation process ourselves. In your average construction site, you must follow the blueprint to the letter while in DIY renovation you can green light things on the spot so there’s room to come up with new ideas on the fly. This approach can make for a very interesting project. Basically, this time I injected a certain ‘design virus’ into a historic building to breathe new life into it.

“Ordos 100” Jun Igarashi, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, 2008

So what do you think about reusing old buildings and materials?

Architecture has no inherent value for simply being old. Reusing any old building should be done solely on a case by case basis.

“Homenaje A Arne Jacobsen” Flitz Hansen, “Seven Chair in Hikari Kukei”, Jun Igarashi, 2015

Your work has taken you to many places so why do you still have your head office located in the small town of Saroma in North Hokkaido?

My grandfather started work as a carpenter and established his trade after the war; it all happened in Saroma. As the third in line of our family business, I began working as an architect also in Saroma. There’s nothing in particular that keeps me there, I just happened to start working in Saroma, and then suddenly, in the blink of eye, all these years had passed without me realising it, and I was still based off Saroma.

In any case, we’re moving our office to Sapporo this Autumn. It was more or less a necessity for our business.

“Osaka Contemporary Theater Festival -Temporary Theater” Jun Igarashi, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, 2005, Photo: Shinkenchiku-sha

Tell us about people and artworks that inspire you.

When I was in primary school, I watched a documentary about Tadao Ando on TV. On the show, they presented the famous ‘Azuma House,’ a terraced house in Sumiyoshi, Osaka, which has its backyard placed right in the middle of the building structure. I was so surprised to see that that house had its inside on the outside and vice-versa, so much so that I had my mind set on living in a place like the Azuma House. Then later on, during a high school excursion, I had a chance of seeing some buildings designed by Tadao Ando in the flesh, even though I didn’t realise those were his designs at the time. I was captivated nonetheless. When I was finally studying architecture, I came across his writings and I was engrossed once again. So I yearned to became an architect just like Tadao Ando. I also admire Kazuo Shinohara, Kazuyo Sejima, Rem Koolhaas, and so many others. Even though he’s not an architect, I’m also a fan of Shiro Kuramata.

“house O” Jun Igarashi, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, 2008, Photo: Iwan Baan

Where would like to go on your next trip?

I want to explore every corner of the globe but right now I’m interested in visiting Sri Lanka.

Lastly, tell us about your future plans and goals.

I would to try many things, to wear many hats. By doing that, I would like discover and open many new doors. As a result, I hope to discover a ‘benign virus’ that transforms Sapporo into a place brimming over with excitement.

Text: Hanae Kawai

Translation: Rafael de Lima