DING YI

PEOPLEText: Hiromi Nomoto

Ding Yi stands apart in China’s contemporary art world. In all his active years, he has consistently created abstract works. Stroke by stroke, he has created powerful works with great depth, as if they expressed the accumulation of his years of experience. From time to time, the fluctuations give a flicker of light. The artist, who just returned from Hong Kong the day before, and is on his way to Beijing, agreed to be interviewed.

I’d like to start by asking about the background to your work. What kind of art or who were the artists that influenced you when you began creating?

It’s very complex. China experienced a drastic change in the 80s. Before, there was no information regarding art, and works considered the best were those from the Soviet Union. In the 1980s, I began studying at an art school, and that’s when I began looking at European and American contemporary art in art books.

What kind of art were you looking at as a student?

At the time, I was drawing landscapes and people. I was also strongly impressed by Utrillo who was an artist at the École de Paris. It struck my heart that his depiction of Paris was similar to Shanghai. I emulated his technique and mindset, and deepened my understanding of western art, including its legacy.

There was a huge change in China, and many (foreign) things were introduced. I began experimenting with abstract art around 1983, and established my own style in 1988. At the time, I was influenced by Mondrian, Francisco Bacon and Stella; I was drawn to them.

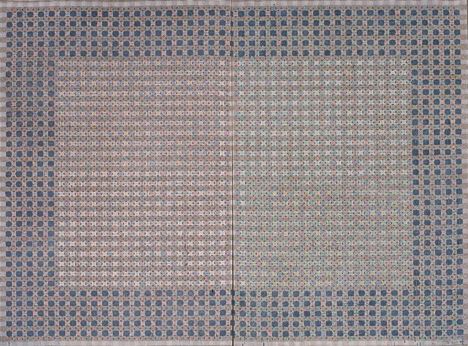

“Appearance of Crosses 1997-8”, 1997, 200x270cm, Acrylic on tartan

Getting to know your work, Mondrian’s name comes up. Why did Mondrian catch your attention?

It has to do with my personality. I am relatively quiet. So I don’t really like to express through emotions. I essentially express art after thinking.

What are the motives behind your abstract expressions?

I’m trying to eliminate western and Chinese traditional paintings. Instead, I’m searching for my own language (to express art). In traditional Chinese painting, it is extremely difficult to accomplish perfect abstraction. Among traditional Chinese landscape artists, there used to exist a concept of abstract expression, but that was not pure abstraction. I knew that I had to search for a new method. Art that is not art-like: something that differs from the traditional art with which we are familiar. I combined art and design. But the first piece I created was not received well.

Where do the crosses, which appear in your work, come from?

This is just the intersection of a horizontal line and a vertical line, or it’s a symbol. I previously studied design. I worked at a toy company for three years, designing packages for toys. There were no computers at the time, and everything was drawn by hand. Grid lines (used to show size on design diagrams) are crosses. That’s where I got them.

Many people refer to your work as “rice (character).” How do you feel about this? Are you conscious of the rice character?

It has nothing to do with the Chinese character for “rice.” I’ve been doing this for over twenty years, so I wanted to add some variation. Rotating and overlapping crosses, the resulting image resembles the “rice” character, but it’s completely unrelated. With two strokes, a symbol like the cross can be created. Adding third and fourth strokes, a character like “rice” appears. And to enclose the “rice” character, eight strokes are used. For me, it becomes more difficult to draw, and the concept becomes even more complex. I’m searching for different possibilities in this system.

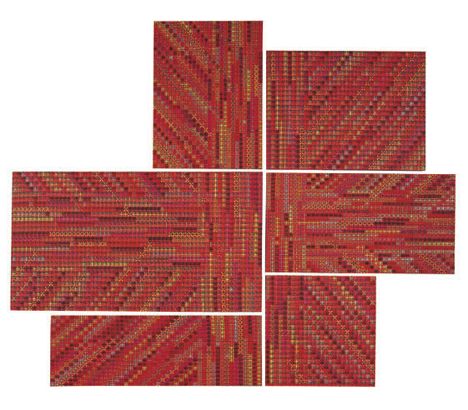

“Appearance of crosses 2005-6”, 2005, 320x440cm, Acrylic on tartan

Your work uses vibrant colors. Is there any significance behind this?

It has to do with my background and the city where I live. My earlier work was mostly painted with black ink. Shanghai in 1988 was dusty and dyed in grey. The city’s colors appeared in my work.

In 1998, there was a significant change in my work’s colors. There was a drastic change in Shanghai, and I looked for intense colors that matched this change. That’s when I began using fluorescent colors. At the time, I made full use of fluorescents. My sentiment at the time was, “a great epoch has arrived (to Shanghai).”

But colors changed after that as well. By 2008, this urbanization was no longer a welcome development; I viewed it as a problem.

I’d like to ask about your use of finished fabrics to make your canvases. I hear you use Burberry fabric.

Ten years into creating crosses, I began looking for a new method. I’ve always drawn plaids. People said I was “drawing fabric.” That’s why I decided to use finished fabric, and transform them into something else.

It’s not always Burberry. When I began (using finished fabric), I looked for fabrics for about a month. I found that Burberry’s fabric was a good fit, because their plaids are perfect squares and use light colors. The lighter the colors, the easier it is to change them.

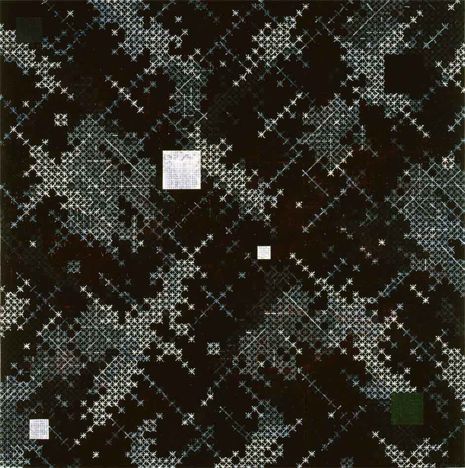

“Appearance of crosses 2006-5”, 2006, 200×135cm, Acrylic on tartan

Big name artists often direct a team of assistants to create their works. You’re highly regarded in the art world and art market, but work alone.

That’s true. I create one piece a month. I have two assistants. One helps out with administrative work and the other assists me in my creative work. The one that helps with my artwork prepares the canvas, but that can be done in a day. So he comes in everyday, serves me tea, and works on his own work. He became an artist.

Why do you create on your own?

Each artist has his or her own production procedure. This is mine.

You are very active abroad through exhibits and the Venice Biennale. Have you considered moving to another country? Or to another city within China, like Beijing?

That’s because my work is intrinsically related to Shanghai. Many people ask me: “Where is your favorite place?” I choose Shanghai without hesitation. People in Shanghai are independent. Artists in other cities meet and dine together everyday. But if there were an exhibit opening in Shanghai today, those who want to join would participate. Those not interested don’t have to go. I like that attitude.

“Appearance of crosses 2011-3”, 2011, 220x220cm, Acrylic on canvas

In the Asian art market, and among Asian audience, concrete art is usually more popular. In such atmosphere, it must have been difficult to create such pure abstract art. Can you talk a bit about that?

It’s true that pure abstract art is not a major art form in Asia, and there haven’t been many trends in the development of Eastern culture. My work was first accepted in the western markets—not in Asia. In the past twenty-some years I’ve been working, there has been a major change in abstract art. Compared to the past, the way in which the younger generation accepts abstract art has also changed.

In Chinese contemporary art, Chinese symbols and images are important, and relations and decisions are drawn out of such images. But abstract art is difficult.

Starting around 2003, I participated in all major contemporary art exhibitions in China. When I participated in the Venice Biennale, Xu Bing (a Chinese artist known for his work depicting the alphabet like Chinese characters) and I were in the same exhibition hall. In my work, it is difficult to portray an image of China on the surface, but other Chinese artists used images of Mao Zedong. Between 1993 and 1994, artwork was introduced in the western media, but not many of my works received attention. Only my name and a small photo of me appeared.

When museums choose artists, they’re pretty fair. I understand “the media’s reaction,” and have decided to move forward on my own pace. I gradually developed my own work.

You have witnessed Chinese contemporary art rise onto the international stage, and watched it develop. You are currently teaching at Fudan University’s Shanghai Institute of Visual Arts. What do you think of today’s young students and artists? What kinds of trends and characteristics do you see?

I think there are two phenomena. The first type seeks market possibilities and imitates earlier artists. The second type studies abroad while they’re in college or in graduate school, and creates more western contemporary art from new angles. These two groups will both create their own paths in the future.

There are many coincidences in art. It has to do with local politics, culture, economies—everything. At a certain point in time, a significant phenomenon or change occurs, and these elements propel people to think.

Ding Yi Solo Exhibition “Specific Abstracted”, Minsheng Art Museum

What are your future plans?

My biggest problem is the pace of progress of my work. I can only create about twelve pieces a year. That makes solo exhibits difficult for me. Preparation for my exhibit at Minsheng Art Museum (“Specific Abstracted: Ding Yi Solo Exhibit” held for two months in 2011) began two years prior to its opening. I haven’t decided on an exhibit for this year. I have been approached for an exhibit in Switzerland in August, but I haven’t replied yet.

Text: Hiromi Nomoto

Translation: Makiko Arima