DONALD RODNEY: VISCERAL CANKER

Rodney often uses (or tried to use) parts of his body as material for his works. The most representative piece of this approach is In the House of My Father. In this work, Rodney’s hand cradles a sculpture made from his own surgically removed skin titled My Mother My Father My Sister My Brother, pinned together to resemble a house. Unlike Visceral Canker, this photographic print of In the House of My Father is rooted in personal memory — it was created after Rodney lost his father to the same illness he suffered from himself.

Donald Rodney, In the House of My Father, 1997, Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre

Both the house and the skin symbolise a place of belonging and serve to protect the body from external harm. Yet, the house is also powerless against police violence, just as the skin is powerless against disease. For example, the infamous Sus Law, which allowed police to arrest people suspected of intending to commit a crime, was unfairly applied to racial minorities in the 1980s. As a result, Black communities were often targeted for excessive surveillance and home raids by the police. The house, fragile enough to collapse in an instant with a clenched fist, seems to suggest the vulnerability of the human body and the social unrest faced by Black communities.

In stark contrast to his earlier works that emphasised his physicality, Psalms (1997) is defined by the absence of the body. The piece features an empty motorised wheelchair equipped with sensors and a camera. It continuously roams the exhibition space, adjusting its course whenever it collides with an obstacle. Rodney created the work as a stand-in because he was physically unable to attend the opening of his solo exhibition. The wandering wheelchair appears lonely and isolated. Yet, its persistent movement — constantly changing direction but never stopping — evokes Rodney’s life journey with the dual burdens of racism and a genetic disease. In this work, the absence of the body is not merely an emptiness. Instead, it makes viewers imagine the presence of Rodney’s body through its very absence.

What is particularly striking about Rodney’s works is that, despite the deep-seated anger toward racism and the despair of losing physical mobility that underlies his art thoroughly, many of his pieces convey a quiet, abstracted rage rather than a loud, visceral outcry. It is important to note that this ‘quietness’ is not born from negative resignation or the inability to find hope in society and life. On the contrary, it radiates a life force that continuously asserts his existence — or his having existed.

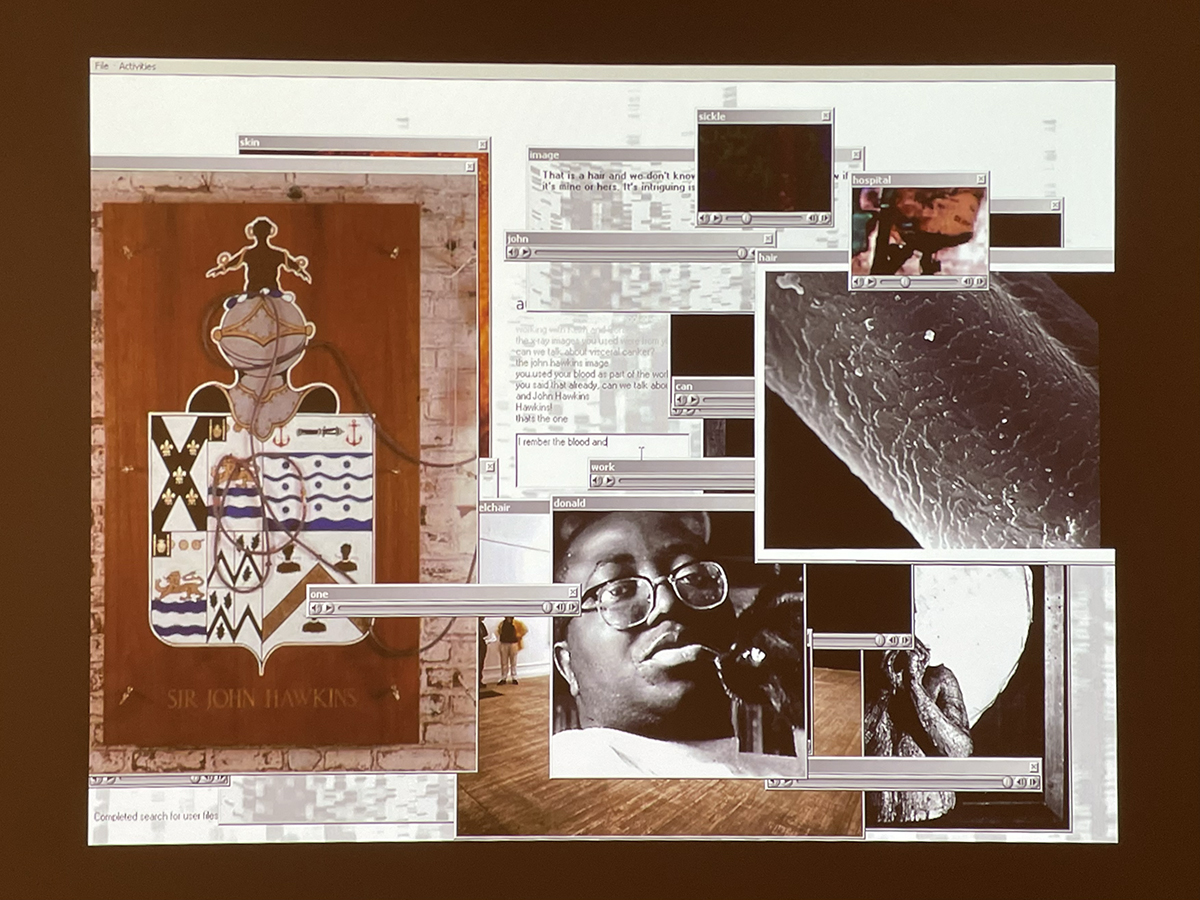

Screen recorded demonstration by Mike Phillips and Gary Stewart, Autoicon, 1997-2000 (demonstration 2025), The Donald Rodney Estate

From this perspective, Autoicon — a project Rodney conceived before his death and completed by his friends afterward — is particularly symbolic. Comprising of a website and a CD-ROM, this work allows Rodney to continue ‘existing’ as a digital entity. Visitors can interact with Rodney by typing messages into a computer, triggering responses generated from a vast archive of medical records, interviews and memories of him.

Considering the material fragility within the Britannia Hospital series, it seems that Rodney deliberately shifted toward ‘leaving traces of life’ or ‘resisting by continuing to exist’ at a certain point. Here, this shift can be understood as resilience — the ability to endure and recover in the face of hardship and adversity — which distinguishes Rodney’s work from the conventional associations of vulnerability linked to ‘disease’ or ‘discrimination’. The word ‘resilience’ emerges as essential to understanding Rodney’s art. Throughout the exhibition, his quiet yet unwavering strength, which refuses to sink into passive pain, is profoundly poignant.

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker

Date: February 12th – May 4th, 2025

Opening Hours: 11:00 – 18:00 (closed on Mondays)

Place: Whitechapel Gallery

Address: 77-82 Whitechapel High St London E1 7QX

Tel: +44 (0)20 7522 7888

https://www.whitechapelgallery.org

Text: Yuki Ito

Photos: Yuki Ito

Proofread: Rose Brennan