LE CORBUSIER: SYNTHESIS OF THE ARTS 1930-1965

HAPPENINGText: Alma Reyes

Referred to as the Master of Modern Architecture, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris or Le Corbusier (1887‒1965) led a robust career spanning five decades as an architect, designer, painter, urban planner and writer. His groundbreaking buildings shaped the core of the modern architecture movement, as well as his theory of color that set the palette for spatial function in building design.

In the exhibition “Le Corbusier: Synthesis of the Arts 1930-1965” currently showing at Panasonic Shiodome Museum of Art until March 23rd, the master as artist, presents his paintings, sculptures, and tapestries, and as architect his phenomenal building projects from the 1930s to 1960s that have made waves across the globe. These accomplishments encompass his poetic approach towards a synthesis of the arts.

Comparable legends Fernand Léger, Jean Arp and Wassily Kandinsky, among others, also display their works similarly resonating with Le Corbusier’s principles of unity, harmony and universal laws. Through the cooperation of Fondation Le Corbusier, Taisei Corporation, CASSINA IXC Ltd, Echelle-1, The Minoru Mori Collection in Tokyo, and other collectors, visitors are able to grasp the totality of Le Corbusier through his dynamic view of the world and execution of the transcendent power of art.

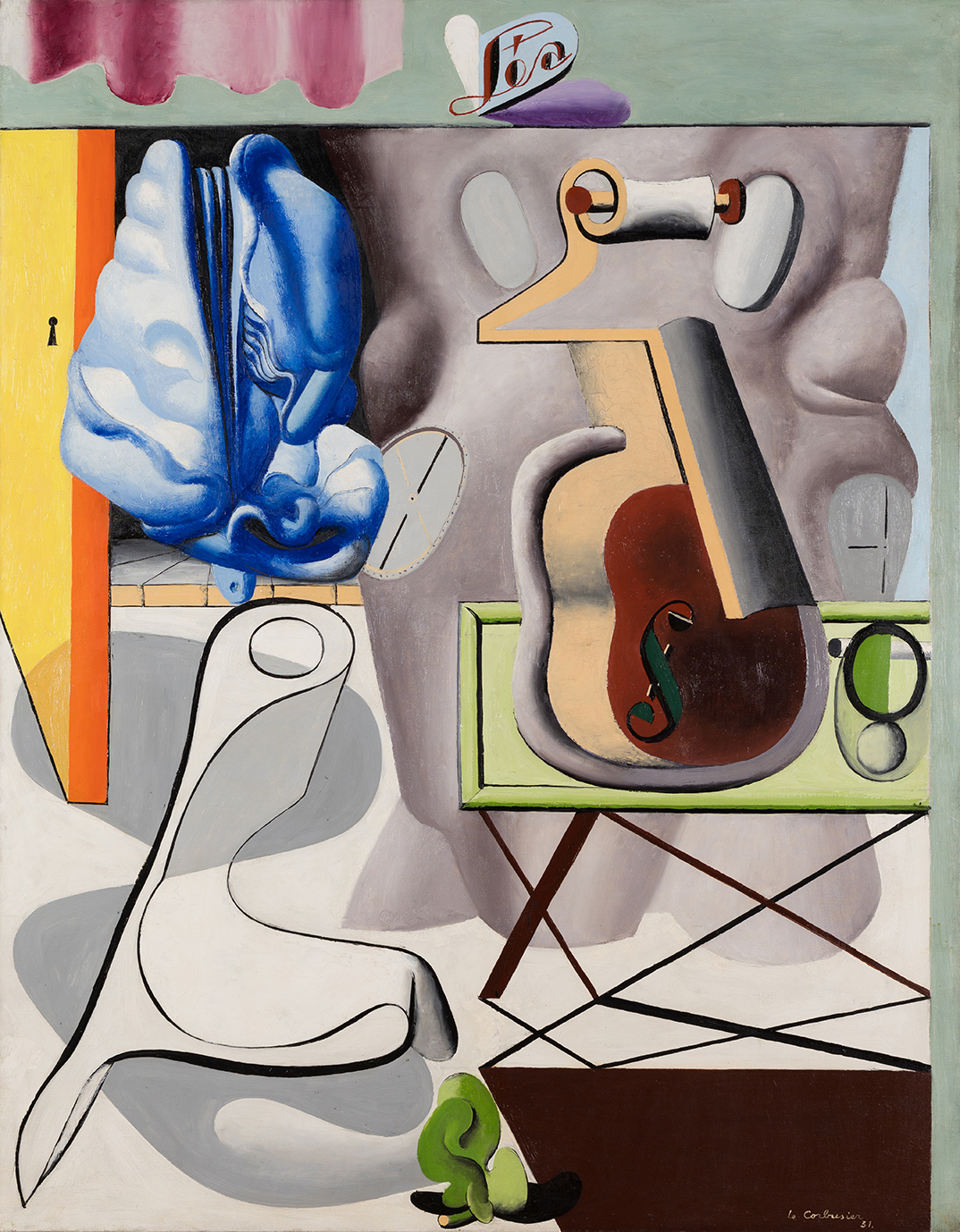

Le Corbusier, Léa, 1931, Taisei Corporation

Le Corbusier embraced organic shapes of nature that included shells, bones, plants, and driftwoods. He possessed a significant collection that he regarded as “subjects of poetic reaction,” several of which are shown in the exhibition. In the section Biomorphism and The Human Body Transformed, works reflect these abstract interpretations of natural forms, many flanked by man-made objects, thereby attesting the correlation between nature and technology. Léa (1931) strikes hints of surrealism, illustrating a giant oyster that peeks through an open door, and a violin on a table in front of a tree trunk. Beside it is a huge cow bone. Next to the colorful painting with parallel features, Léger’s Composition in Green (Composition with Leaf) (1931) describes a long, bold green leaf, against a tree trunk, and mixed with screw-like parts and scrap iron. Both artists share dreamlike images that feed the subconscious with organic and industrial objects.

Le Corbusier, Two Women and a Matchbox, 1933, The Minoru Mori Collection, Tokyo

Further, in the same room, Le Corbusier’s Perilous Harmony with Lantern (1931) also gathers daily objects — pot, matchbox, cigarette, hexagonal glass, and a lantern at the center of the picture. Contrast is expressed in the warm pot versus cold glass. The exhibition poster’s main artwork, Two Women and a Matchbox (1933) delineates a woman’s distorted body, resembling a shell, on the right, and her brunette hair and enormous hand lurking into the black space behind the open door above. Such twisted human forms correspond to organic shapes, which highly inspired the artist. Likewise, in the middle of the room, Arp’s marble sculpture Mediterranean Group (1941/65) emphasizes the fluid union of human configurations and natural shapes. Visitors can circle around the piece endlessly and imagine varied images, perhaps, a driftwood, or a group of dancers joining hands.

La mural nomade installation view, Fernand Léger, Birthday, 1950, The Museum of Modern Art, Saitama / Le Corbusier, Strange Bird and the Bull, 1957, Taisei Corporation / Le Corbusier, Still Life, 1965, The Minoru Mori Collection, Tokyo, Photo: Alma Reyes

In the late 1930s, Le Corbusier shifted to larger formats exuding more vibrancy and lucidity and bolder color compositions. Towards the 1950s, he envisioned his philosophy of “synthesis of the arts,” which entailed the unified framework of furniture, daily objects, sculptures, paintings, murals and tapestries that stimulate the senses in a poetic environment. He remarked, “There are no sculptors alone, no painters alone, no architects alone. The plastic event is accomplished in a ‘ONE FORM’ at the service of poetry”. He became involved in creating movable tapestries, which he called “nomadic murals.” His intention was to make the murals easily “detached, rolled, carried under one’s arm, and hung elsewhere.” One room is dedicated to three vast tapestries — one by Léger, and two by Le Corbusier — which are enlarged reproductions of his paintings based on life-size sketches. At the center is Strange Bird and the Bull (1957) and on the right, Still Life (1965), both highlighting common motifs, such as bull, hands, rock, pitcher, and other objects found in daily life. His tapestries had become architectural pieces that converted walls into works of art.

On the subject of bulls, visitors should not miss the Private Mythology section, showcasing the artist’s renowned canvasses, Bull XVI (1958), Bull XVIII (1959), and Bull (1963). It was said that Le Corbusier became fascinated with the animal during his numerous trips to India. He produced a series of about twenty works, which magnified his private poetic dream world. The creations manifested symbols, such as “the hand that is open to give and open to receive.” Profound messages of anti-establishment, violence, and war could also be felt in the depiction of large horns and nostrils.

Read more ...