THE 6TH BERLIN BIENNALE

HAPPENINGText: Yoshito Maeoka

In mid-May, posters plastered all over the wall of a building near Moritzplatz caught my eye. The posters were portraits of women and close-ups of their body parts shot in black-and-white with white and saxe blue borders. They looked like advertisements for an apparel company. However, there was no accompanying text informing for what purpose the posters were hung; the posters were a mystery.

But among Berlin art fans, these posters were tacitly understood. These were the images of Michael Schmidt’s “Frauen” series that popped up when one accessed the Berlin Biennale website. In addition to the posters, these photographs appeared on catalogues and other handouts. They became eye-catching images representing this year’s Berlin Biennale.

According to curator Kathrin Rhomberg, these posters intentionally aimed to generate questions that demanded explanations: Are these advertisements? If so, advertisements for what? If not ads, what are they? With such schemes incorporated into this year’s exhibition, my expectations for the 6th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art—which was aptly entitled, “what is waiting out there / was draußen wartet”—swelled.

Alte Nationalgalerie ⎮Old National Gallery

In addition to the exhibition space at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, which organized the Biennale, this year’s festival was held across 4 main venues in the southern district of Kreuzberg. At the Old National Gallery, guest curator Michael Fried presented an exhibition centered on 19th century realist Adolph Menzel’s drawings, whose pursuit of realism appropriately fitted the exhibition’s main theme.

Below, I will share some of the artwork exhibited at KW and the abandoned building space at Oranienplatz with the hope that readers will get a sense of the atmosphere at this year’s Biennale.

Petrit Halilaj

At KW, a series of Petrit Halilaj’s works were displayed in a way that implied its position as the induction into the exhibition. The venue’s usual entrance was blocked, and attendants directed visitors to a staircase descending to the basement. The dark underground tunnel led to a spacious hall with high ceilings, crammed with wooden structures. The constructions were based on the artist’s home built in the chaos of post-civil war Bosnia. Aside the construction work, there was an open door that led to a courtyard where a chicken roamed freely.

Petrit Halilaj

This wooden structure took over the first 2 floors of the venue. One could view a part of the construction from outside of the widow, which was left open for the sole purpose of viewing the one segment. With the rest of the floor simply painted white, space was used quite lavishly for this exhibit. On the 1st floor, drawings and installations with chicken motifs were displayed. In other words, of the 3 floors of KW’s exhibition space, Halilaj utilized nearly all of it, as if it were a solo exhibit (KW’s solo shows usually take up similarly large spaces).

Mark Boulos

In his exhibit, Mark Boulos projected footage of the Chicago Stock Exchange, which handles some of the largest derivatives exchanges, on one wall, and a recording of Niger Delta inhabitants’ lives on an opposite wall. As exchanges over the Royal Dutch Shell group rapidly take place, scenes of inhabitants impoverished due to fisheries polluted by oil fields were projected simultaneously.

Oranienplatz 17

On Oranienstrasse, the Kreuzberg district’s main drag, there is a building that has been vacant for years. Oranienplatz 17 is a 5-story building. While the catalogues and other literature do not disclose the history behind this edifice, it was constructed as a shopping center before the war. After the war, aside from the 1st floor’s stint as a supermarket, it has hardly been used.

Marcus Geiger

Devoid of interior renovations, original paintjobs and facilities remain intact inside the building. Glimpses of history are visible in the old floor patterns as well. Gedi Sibony’s installation suited the bareness of a building paralyzed in time. Even Marcus Geiger’s 1996 “Kommune” appeared like an abandoned rug (several visitors were witnessed actually treading on this artwork).

Adrian Lohmüller

From the naked walls of Adrian Lohmüller’s installation, a pipe along the ceiling conspicuously stood out. These pipes were fixed on every floor of the building, and water ran through them from buckets and tanks. The piping led to a gas burner on the 2nd floor where the water was slowly heated. The water was then distilled through the pipes, and dripped onto salt crystals. At the end of the water droplets’ trip, a set of bed linen was laid out. Throughout the duration of the exhibition, these drops were to crystallize from the salt.

Hans Schabus

Hans Schabus borrowed large dinosaur models from the abandoned amusement park, “Spree-Park Plänterwald” in eastern Berlin, and transported them into the courtyard. The former amusement park was constructed in East Berlin, and was loved by its citizens as the leading recreation complex, but closed in 2001 due to financial difficulties.

Anna Witt

There were numerous videos on display at this venue. Below are 2 of my favorites.

A naked Anna Witt submerged herself in her mother’s clothes, and climbed out of the stomach, capturing a performance of her own re-birth on camera.

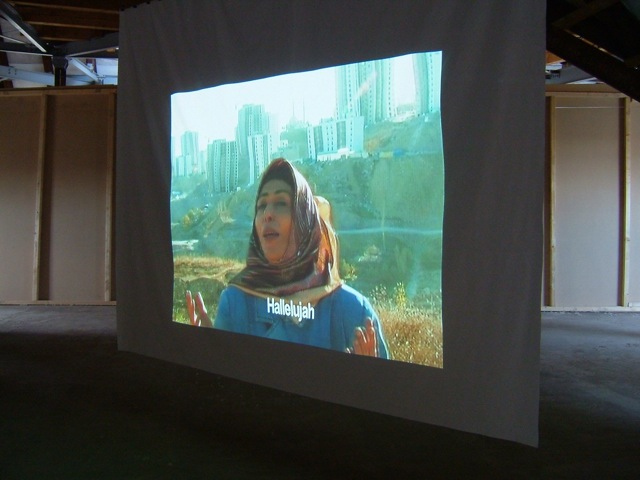

Ferhat özgür

In Ferhat özgür’s piece, a traditional Muslim-looking woman wearing a scarf sang along to Jeff Buckley’s Hallelujah, originally composed by Leonard Cohen. After I viewed this exhibit, which was projected on the top floor of the venue, I glanced out of a window. There, similarly dressed women were enjoying the afternoon on the balcony opposite the venue building.

Danh Voh

Danh Voh was born in Saigon in 1975, after the end of the Vietnam War. He transferred to Denmark, and now lives and works in Berlin. In his studio, located 5 minutes away from Oranienplatz, he reproduced the plant drawings of Jean-André Soulié, a 19th century missionary in Indochina and Tibet, onto his bathroom walls. He also transcribed Soulié’s last letter, and laid it out on a table in his study. As if retracing Soulié’s life in Southeast Asia right in his apartment, one could detect traces of the missionary’s life along with hints of the artist’s daily life. While I have seen many artists attempt to turn their studios into exhibition spaces, Voh’s ability to integrate disparate objects into his work—his ready-made style—seemed to give everything in his studio, from his furniture to cooking utensils, stories of their own. This made for an enjoyable viewing of his workspace.

I found the absence of artists’ nationalities on captions and in the catalogue a notable aspect of the exhibition. Artists like Dan Voh and Olga Chernysheva were born in Vietnam and the Middle East, respectively, and have subsequently resided in different countries. Their nomadic pasts, in fact, are vital factors in their work. The omission of nationality labels could be an acknowledgement of the prevalence of modern artists whose work span across national borders. It could also be understood as a message to the other Biennales that boasted “international diversity” from the reality that is “outside of art.”

Looking back at the Biennale, as a whole, the question of what is “outside/ draußen?” remains. How has art portrayed reality? This may have been the theme for the exhibitions, but with such a large group of artists, the answers are inevitably ambiguous. And though it has been the recent trend in large exhibits, 1/4 to 1/3 of the works were video art.

In the 4th and 5th Berlin Biennales, there were, in some shape or form, allusions made to the city of Berlin that was the backdrop to the festivals. This year, excluding a handful of artists like Hans Schabus, it appeared as if the exhibitions avoided making direct references to the city. By focusing on the world of art, the Biennale may have intentionally expunged the reality of Berlin from the artistic realm.

Press conference

At press conferences and at the opening, an intangible difference in attitudes could be detected between residents of this year’s main venue of Kreuzberg and the art journalists and visitors who flocked to the Biennale; it was like a line was drawn between the “outside” and the “inside.” Also, visitors stood in sunlit exhibition spaces, quietly viewing video art while many protests and demonstrations took place outside, and other areas were in the midst of the World Cup excitement.

What was exhibited at the Biennale could also be a warning to the somewhat cloistered city of Berlin. The gap between the “outside” depicted in the artwork and the heat from the reality of the city made a compelling case for reexamining my own position and perspective as well.

The 6th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art

Date: June 11th – August 8th, 2010

Place: KW Institute for Contemporary Art, other venues in Berlin

https://www.berlinbiennale.de

Text: Yoshito Maeoka

Translation: Makiko Arima

Photos: Yoshito Maeoka