THE WRIGHT IMPERIAL HOTEL AT 100: FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT AND THE WORLD

HAPPENINGText: Alma Reyes

When we think of the most paramount pioneers of 20th century modern architecture, the name Frank Lloyd Wright is undoubtedly unmissable. With an astounding record of over 1,100 designed structures in a period of 70 years, Wright’s uncompromising emphasis on “organic architecture,” which, by his concept, respects the unique circumstances of a building’s origin, topographical location, its builders and methods of usage had been well accounted for in such famous projects as the Edgar. J. Kaufman House (Fallingwater) and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Exhibition entrance, Panasonic Shiodome Museum of Art, Photo: Yukie Mikawa

In Japan, Wright had planted numerous seeds of achievements – the Imperial Hotel (partially relocated and preserved at Museum Meiji-Mura), being one of his most outstanding legacies. Celebrating the centennial of the 1923-established hotel, Panasonic Shiodome Museum of Art is presenting The Wright Imperial Hotel at 100: Frank Lloyd Wright and the World until March 10th this year. The grand exhibition particularly highlights the sources of inspirations that drove Wright to design what has been praised as the first authentic total work of art combining Western-style living and aesthetics since the introduction of the Arts and Crafts Movement into Japan. The exposition, also marking the architect’s first showcase in Japan in 25 years, introduces architectural plans and drawings, photographs, scale models, furniture, tableware, interior fixtures, and video clips loaned by Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library at Columbia University, and collectors and museums in Japan and abroad, summarizing a full retrospective of Wright’s magnanimous contribution to architecture and arts and crafts.

Exhibition view, Section 1, Modern beginnings: Chicago-Tokyo and the culture of ukiyo-e, Photo: Yukie Mikawa

Wright’s destiny to become an architect was pre-determined by his mother even before he was born. From rural Wisconsin where he studied Civil Engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he moved to Chicago in 1887, and became an apprentice of Joseph Lyman Silsbee, then moved to the firm of Dankmar Adler & Louis Sullivan. Sullivan’s firm principles of organic growth, spatial balance, and rhythmic enhancement of the interior greatly influenced Wright’s detailed attention to ornamentation and natural elements. The first section of the exhibition presents the architectural scene in Chicago from the late 1800s that had shaped Wright’s robust career.

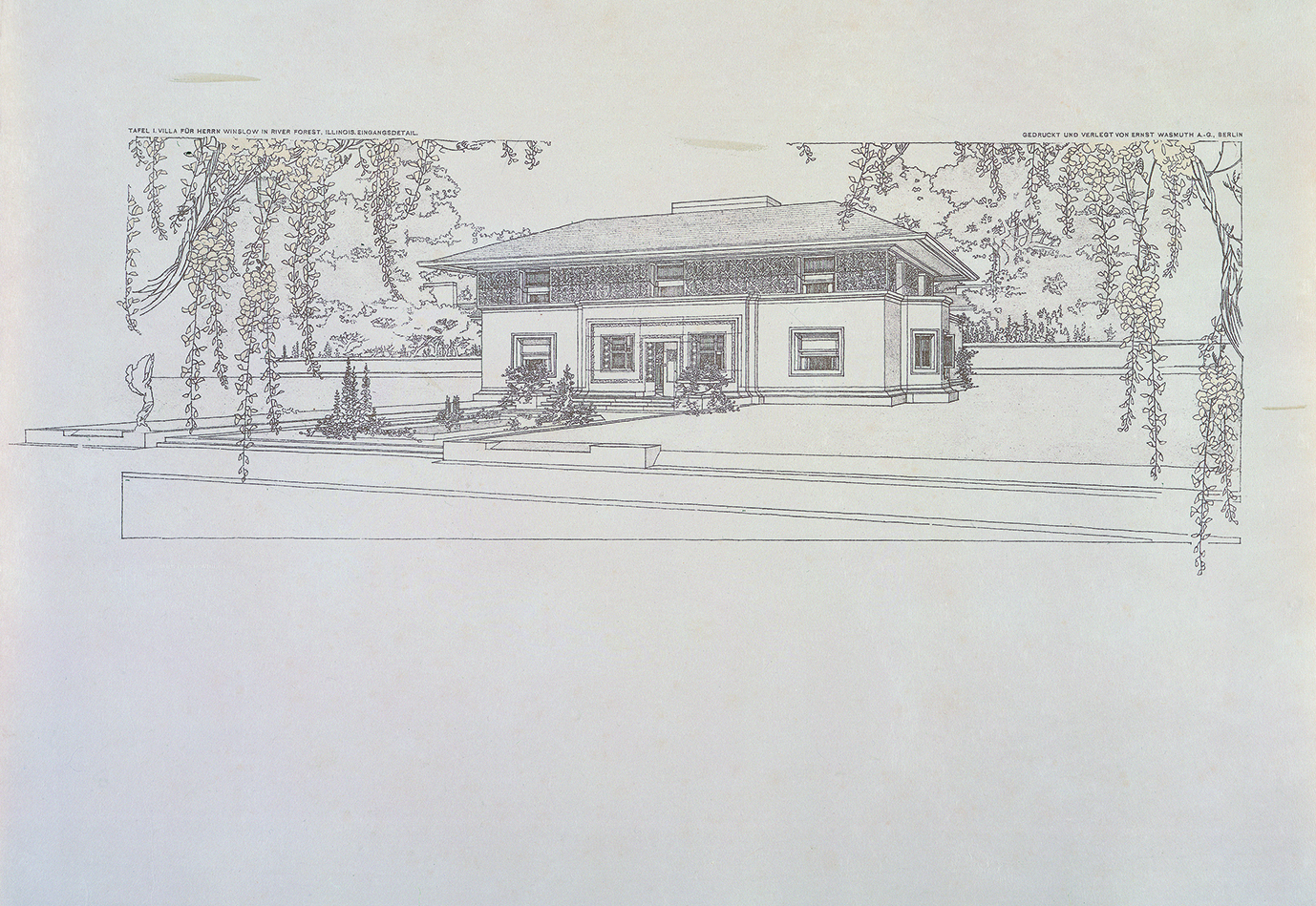

Frank Lloyd Wright, Plate I. Perspective of Winslow House, River Forest, Illinois, Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright, 1910, Ernst Wasmuth, publisher, 1901, Toyota Municipal Museum of Art

Instigating the connection between materials and nature, Wright’s first work as an independent architect was the Winslow House (1893-94), which projected his known Prairie style, consisting of horizontal lines, flat or hipped roofs, wide overhanging eaves, and use of natural materials, such as stone, wood and brick.

Wright’s Welsh heritage and religious background (his father, a Universalist minister, mother, a member of the Oak Park Unity Church, and uncle, a Unitarian preacher) posed certain links with the commission to design the Unity Temple (1905-08) in Oak Park, Illinois where he himself lived and worked. Limited by budget constraints, Wright chose concrete as the building’s principal material, which nevertheless, evoked traditional Western ecclesiastic architecture. Fresh from his first visit to Japan in 1905, the building reflected features of the Gongen-zukuri style of Japanese shrines, and his drawings of Ukiyo-e compositions and motifs. It was regarded as the architect’s first public building work.

Read more ...