CALL ME THEY

PEOPLEText: Alvis Choi

What happens when a Blowfish falls in love with a paper plane? In their transgender art blog “Call Me They”, Canada-based artists Elisha Lim and Coco Riot create their original art of video, stop-motion animation, comic, illustration, clay-animation etc. to celebrate trans queer love and to advocate the use of “they” as a gender-neutral pronoun. They define trans ‘not as in “she becoming he”, or “he becoming she” – but trans as in neither he nor she, as in “they becoming they”’. I talked to them about their inspiring work.

Elisha Lim and Coco Riot, 2011.

Please introduce yourself.

Elisha Lim (E): My name is Elisha Lim and I’m Chinese-British. In Canada, people think I just look Chinese, which makes them treat me differently: ignore me, condescend towards me and rarely consider me for a position of leadership. That really pisses me off. It has turned me into a fighter – against racism in general. It also makes me think of queer racialized people as my beloved extended family. My art is all about this: love, pride and resistance.

Elisha Lim, 2012.

Coco Riot (C): My name is Coco Riot and I’m a Spanish queer artist living in Canada. Most of my art consists of different forms of narrative drawings that allow me to express my personal and political experiences. As a Spanish-speaking queer I have set my goal to be part of a queer culture that speaks and feels my language and decentralizes queerness from the very Anglo-centric point of view where it is now. I guess, another goal is to make beautiful things, whatever beauty means for each of us. I feel, in our communities, beauty may be a way of healing and self-care.

Blowfish, Elisha Lim and Coco Riot, 2012.

Can you explain about using “they” as a neutral pronoun?

E: We both use the pronoun “they”. It’s a widely accepted and popular trend in our queer subculture. It’s because we reject the boring idea of only two genders. Right? We all know people who are “a little too butchy for a girl” or “a little too girly for a boy.” And when we look at history, lots of indigenous cultures use a range of words to describe gender, in Southeast Asia, India, North America, Central and South America, lots of places. They don’t stop at two. So in our English-speaking queer scene, people started using “they” as a third option, a neutral option, and it has gained a lot of traction.

*Note: In case you are wondering, “they” as a singular pronoun is totally grammatically correct. Watch this video to learn about it.

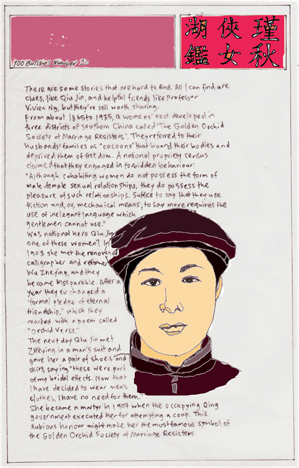

100 Butches #20 Qiu Jin, Elisha Lim, 2010.

Please tell us the origin of Call Me They.

E: Coco and I kind of got thrown into “They” activism. I was interviewed by Canada’s biggest gay newspaper Xtra!, and they refused to use “they” as my pronoun. They sort of laughed at it, and said it wouldn’t make sense. That was a mistake, because ‘they’ is a popular queer movement, and as a gay newspaper they can’t afford to annoy so many of their readers. I knew that. So to force them to use “they,” Coco and I started a Facebook event about it. Sure enough, 1,350 people joined it within a couple of days. So the newspaper backed down, and we became public leaders in the movement.

Then we thought, let’s put all of our personal gender experimental art together into this blog, Call Me They, and use it as a central station for art lovers and “they” folks to enjoy. The best part though, is the videos. That’s my favorite.

C: Yes, that’s true. We also made a video where we question the pronoun “they” because we are aware of its limitations and we want to bring also this criticism. For example, we talked about its colonial aspect. We had a long discussion about it, and maybe you want to watch it online and get back to us.

Blowfish, Elisha Lim and Coco Riot, 2012.

Tell us about your background? What was your training in art if any? If not, how did you start making art and how did you become an artist?

E: I didn’t have any training. Nope. None. In fact I’ve been rejected from every art school I’ve ever applied to. I started drawing because I saw an ad for a comic artist in a lesbian magazine. I think I became an artist when people started asking me to talk about it. They said it touched them, helped them feel a sense of belonging and worth. That makes me extremely proud! It makes me want to make more. So I did, and since then I’ve had solo shows and group shows in Canada and the States, and I’m curating my first show in Montreal this summer: 2-QTPOC. You know what that means? Queer and trans people of colour baby! With a special emphasis on 2-Spirit, which is how some Indigenous communities of Canada called folks who were both female and male. Yay!

C: For me, I have been drawing forever. I remember I used to copy and copy the same paintings once and again when I was a child. Then I started making cartoons because I love telling stories, and then I started making zines, self-published magazines, with those queer cartoons. As an academic background, I studied literature, and then one day, I decided what I really wanted to do was to quit my job, study art and do more drawings. So I applied to the National Art School in Toulouse, France, where I was living. I got accepted and I quitted my job and made more and more drawings. But I do think art is not about art schools, I think art is about having a community. As artists we do need to talk to other artists, to other people doing things, to the audience. Art comes from this dialogue. I think I became an artist because I had people to show my drawings to, and people told me what they thought, and then I told them what I thought about their art. And we didn’t agree all the time! Which is great! So I guess I would say my most important art school has been my communities, my peers, my friends, and also the well-known artists with whom I have a discussion in my head when I’m seeing their pieces!

The Hawker, Elisha Lim and Coco Riot, 2012.

Which is your first video? How did you start making stop-motion animation?

E: It’s called The Hawker. I was like “hey Coco, come here and direct this video.” Coco was like, “I’m sleepy,” but did it anyway. We did it with lots of transgender love, stop-motion and bright colours. Now we’re very happy that it’s been programmed all over the world, in Toronto, Chicago, Los Angeles, Berlin, Singapore, and in Seoul!

C: Hahaha, yes it was like that! I said I would only do it if we clearly separate the jobs: you write and I direct. At the time I have spent what seemed ages in a short animation video called Uprooted, for which Elisha made the music. So I guess I was very tired of animation, it’s sooooo complicated and slow! Stop-motion is a “faster” way of animating. It also seemed the best technique for the story Elisha wrote. It allowed us to make drawings, introduce our every-day objects and narrate stories based in real-life but where we can open an imagination window. I think The Hawker achieves this perfectly: it is touching, personal, inspiring.

We are extremely proud of this film. It started as an evening activity and now it has been screened in huge screens all over!

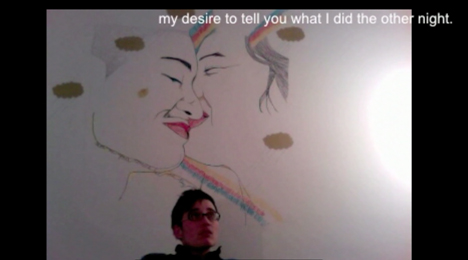

My Culture, Elisha Lim and Coco Riot, 2012.

Elisha, I remember talking to you about the video My Culture and thought that you were referring to the traditional culture in Singapore where you grew up as a teenager, but I was surprised to learn that you were actually referring to North America. Maybe you can tell us more about this video?

E: Hee hee! It’s actually not about conservatism in my mind. I was trying to prove that North America is an exotic place. It tries to sell itself as the centre of the world, and all the rest of us are exotic. But it is foreign and weird and full of curious rituals. And in particular, I wanted to poke holes in the fallibility of its gender logic.

What about the queer culture in Singapore and Spain?

E: I haven’t lived in Singapore for so long, so all I have is distant teenager nostalgia…But I do my best to remember how it felt to arrive here in Toronto. I remember that the Toronto Pride Parade felt kind of wrong. There were so many placards and rules, about Lesbians and Gays and Straights. Lots of “Us” and “Them”, which is exactly what I do now with race, haha! But at the beginning, I really disliked it. I think it’s because as a kid in Singapore, I was queer and knew lots of queers. But we didn’t turn it into an argument. We didn’t let it get in the way of working together with each other as a class or a school or religion or country.

Man, it makes me sad to remember. That was a beautiful way to be. I know I’m being nostalgic, but I’m trying to be humble too. There’s a wisdom about those Singaporean memories that I should probably try to learn from.

C: Spain has a long story of “queer” activism. Of course we have never called it “queer” because this is an English-term that does not mean much for Spanish organizers. Sadly, we are forgetting the history of those activism and we are trying to paste North-American queer politics onto Spanish realities, erasing any trace of any queer activism that has been happening for ages in our organizing culture and history. When you paste North-American queer politics onto Spanish experience, it doesn’t make much sense, because there is a disconnection with peoples’ realities. I’m happy to see the creation of a huge network of Spanish-speaking queer activists, groups, ideas, culture, etc. between people living in different Spanish-speaking countries. There is this desire to reconnect with a queer activist tradition that is rooted in, for example, Cuban gay literature, Argentinean queer films, Colombian feminists actions, Spanish anarchist traditions, etc. In my art I position myself within this Spanish-speaking queer culture. For example, I made this one-month tour with my book Llueven Queers, which is the first ever Spanish queer graphic novel. I was hosted in every city by queer organizers and every night I was meeting new ways of queer organizing because of the different cities and audiences coming to the book presentation. My experience with Spanish queer is that it is rooted in anti-capitalist traditions, mostly anarchist, and that is less about a life-style than a constant struggle (at many times violent ones) against the order imposed on us by the State, by the church, etc.

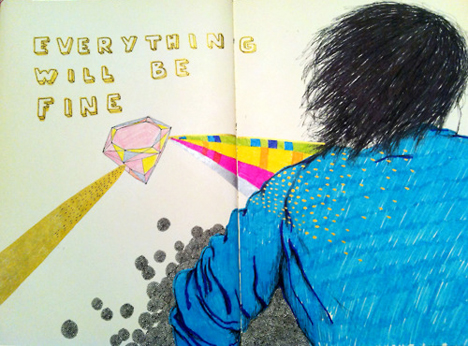

Everything Will Be Fine, Coco Riot, 2011.

All of your videos are very heavily text-based. The voiceover in each of your videos is amazingly moving. Can you tell us more about this strategy?

E: Thank you Alvis! Storytelling is extremely important to me, and Coco and I try to train and challenge each other to tell stronger stories. It’s so easy to tell a story with lots of wasted, self-indulgent detail. It’s hard to tell a story that’s simple and true. I really treasure having the chance to tell people stories. It’s a moment of child-like wonder and security. It actually matters to me more than the images – I call myself a ‘story decorator.’

C: Oh Alvis, I never thought it was a strategy, but yes, you are right, it is! I think Elisha has a very strong quality voice that allows them to connect with the audience, not only from the narrating point of view, but also the emotional one! I think our best stories are the ones that Elisha writes and narrates. Elisha is an amazing writer, performer and musician. Usually Elisha will write a story and I will think of the images for it, but I don’t like being stuck to the narration, I don’t want images to be the illustration of the voice, I want the images to expand the story. I guess in a way, the voice, the story keeps the path, they are the main element of our videos, while the images are there to open possibilities.

Los Sentidos, Elisha Lim and Coco Riot, 2011.

What is the agenda for Call Me They? What do you think you have achieved so far and where do you want it to go? What is it that you want to change?

E: Good questions! I love the challenge! Let’s see. The agenda is basically to stay alive. Do you know what I mean? Especially as a queer Asian, there aren’t many reasons for people to listen to me. So a radical, ongoing blog is a good way to keep talking, keep connecting, keep encouraging and supporting other people like me.

I’m not satisfied with what we’ve achieved. I think that we’ve achieved a bit of popularity and celebrity. But it really misses the point. I think North American queer communities are very prone to celebrity culture. It’s not their fault, but that is a superficial thing.

Coco and I talked about bringing other artists in, or inviting folks to submit stories for us to animate. If this blog became a showcase for other marginalized transgendered queers, I would like that.

Setting up for the first Call Me They exhibition at Venus Envy Ottawa, February 2012.

Do you identify yourself as a radical queer? What is the relationship between your politics and your art?

E: I do, I do! I’m very proud to come from a long radical queer racialized tradition!

C: Oh yes, I identify as a radical queer and I hope my art reflects my ideals. As I said at the beginning, bringing “beauty” is another radical element of my art and my politics. We can discuss for hours about this idea of “beauty”. I guess for me, “beauty” means a place for us to rest for a second from our everyday fight, and a space to be proud of who we are. I make art to make my communities proud.

Can you tell us about your creative process as a collective? E.g. how do things work between the two of you?

E: Hahahaha! We quarrel all the time. We are both very conceited and sensitive. We had to insist on clear roles: for this film you are the director and I am the writer, next time will be vice versa. But we love each other, which makes it really exciting. We will sit in a festival cinema with our videos playing, and we will get to hear people gasp, and feel the little bits of magic that we had hoped for, and because we love each other, we feel even more magic and happiness for having created this moment. At the end of the day we’re just very proud of each other, and that makes it fun to keep working together.

C: Yes, that’s exactly how it is. I have learn’t to let go of my control because Elisha has taught me they are a genius. Collaborating is about trusting each other. This is very challenging for us, because we are both used to doing everything by ourselves. And let’s be honest, we are very stubborn. But, seeing the results, like watching The Hawker on a screen, as Elisha said, it’s magic. It’s worth all our quarrels.

Los Sentidos. Stills collage by Coco Riot, 2011.

Can you name a few artists or queers who inspire you?

E: Yes definitely! These queer racialized artists that make me believe that change is possible, that we are beautiful, and that we can demand respect: Kent Monkman, Kama La Mackerel, Leroi Newbold, Richard Fung, Sameer Farouq, Barbara Cameron, Alaska B., Ange Loft, Jin Haritaworn, Adee Roberson, Textaqueen, Ian Rashid, James Baldwin, wow, so many people. I feel very lucky to have discovered each of them.

C: I am very inspired by what I see around me in the street. I love looking at posters, at people houses’ decorations, at clothes. I love fabrics and patterns and I am very inspired by the bright colours and patterns of traditional forms of art in Spain, for example the Alhambra ceramic decorations or the narrative baroque sculptures. I think I am very inspired by what my communities and friends produce in terms of art, for example I love Montreal-based Jenny Lin’s books and animations, Barcelona-based Susanna Martin’s comics, Elisha Lim’s portraits, Coral Short’s community performances. I am very lucky to be friends with such amazing artists, because I can ask them all the questions I have and I know we have strong admiration for each other. In terms of art history, I really like narrative drawings, for example old Flemish paintings and Persian manuscripts drawings.

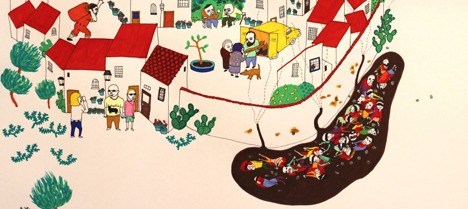

Los Fantasmas, Coco Riot, 2012.

What are your upcoming projects?

E: Actually, lately I’m interested in God. I know, that does not sound like art at all. But my art and my queerness have made me feel a special kind of freedom. I don’t feel ‘accepted’ by the mainstream, and I see that it is a luscious and thought-provoking position. And while I’m out here, I’m interested in a radical spiritual worship, broken out of the mould of any organized religion. I’m working on a movie now where I draw the faces of six queer people on the subway, while simultaneously, there is an audio recording of their most intimate prayers. I feel happy and encouraged by the Quebec Arts Council, who awarded me a generous grant to pursue this. I can’t wait to see its public reception.

C: I am now working on my most challenging project ever. It is called Los Fantasmas and it is a 24 metres mural about Spanish mass graves history and the denial of this part of very recent history (1936-1975). Spain is the second country in the world with the highest number of mass graves, but this is a public secret we have learnt not to speak about. I am interested in how this secret of torture and murder impregnates the everyday life of present Spain. I also received a grant for this project, something that would have never happened in Spain. I am working on it now to show in Canada, but my goal is to have an exhibition in Spain.

Anything you would like our Japanese readers to know?

E: I would like to say please come and see my website and write to me. Challenge me, demand something from my work. When I lived in Asia, I saw the West as the producer of culture, and myself as a consumer of their culture. I regret that now. It’s hard to come across a non-Western point of view! I would like to hear it.

C: Japan has such a long tradition of narrative drawing, something I am very interested in. I am looking forward to meeting artists and organizers who work with narrative drawing as a way to express their politics! Please visit my website and get in touch!

Text: Alvis Choi

Photos: Elisha Lim and Coco Riot