TAKASHI IKEGAMI

PEOPLEText: Yu Miyakoshi

Science and art: when those two domains converge, is it oriented towards scientific intuition or towards artistic conception? Neuroscientist Kenichiro Mogi has said, “An artist is a wild animal; a researcher is a wild animal trainer,” but complex-systems researcher Takashi Ikegami, currently a Tokyo University professor, and drawn to the field of art, tries to be both. An interview with Ikegami is absolutely like seeing from his perspective the deep forest of science and art.

In 2005, after being a long time researcher, you created an installation, with musician/composer Keiichiro Shibuya, called “Description Instability,” at ICC (NTT Intercommunication Centre). After that, while continuing to be a researcher, you have evolved as an artist, with your participation in man-made soundscape installations at the YCAM(Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media), such as filmachine (2006) and Taylor Couette Flow (2007). Could you tell us what attracted you to the field of art?

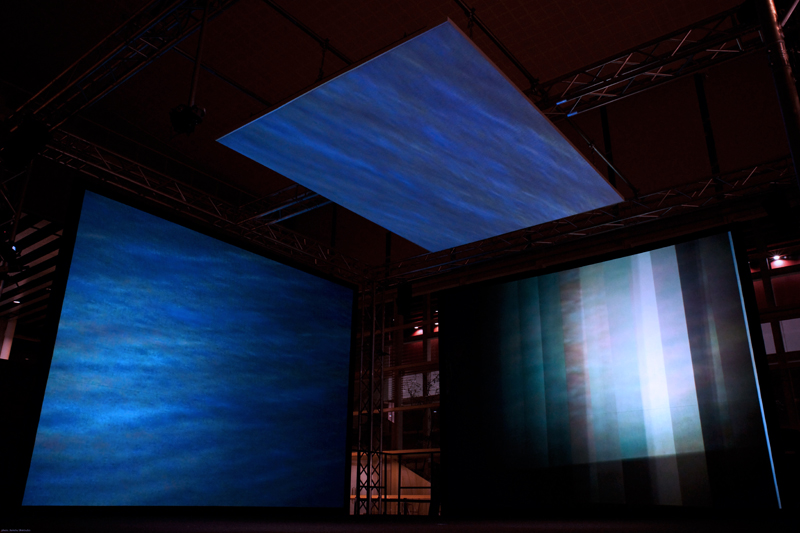

It was simply because when I met Keiichiro Shibuya, we got along so well. Till then I had never actually thought of working in art. In 2005, we made a machine named the Third term music machine*. For the installation filmachine, I used a sound file created by using an algorithm from my research, and Shibuya made a musical composition from it. Filmachine is a three-dimensional soundscape, but it could not have been made without the help of sound artist Evala; Ogai Yuta, a PhD (doctor) working in the lab at the time; and Maria, who was in charge of the project.

*Third-term music: Usually “music” is drone and melody, that is repetition and variation of sounds. A new third element is unconsciously created by the composer or by the accidental harmony of each sound.

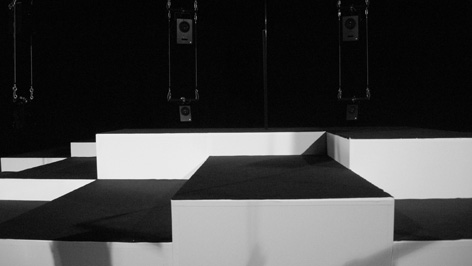

“Description Instability”, Concept & Composition: Takashi Ikegami, Keiichiro Shibuya (2005)

Another machine you made “Taylor Couette Flow” that was used in the same name show of you and Shibuya. I thought it was amazing. In grappling with art, you talk about ‘making a natural phenomenon’. What do you mean by this?

I believe the best way to know about nature is creating a artificial system. For example, people who live in the city surrounded by all sorts of artificial products and the internet are more aware of the real nature. Actually Taylor Couette – a machine that creates its own turbulence — is not my idea; it was invented by two scientists, Taylor and Couette, more than 70 years ago. Water runs between the double layer of a circular cylinder. When the inner cylinder rotates, the water runs faster and as speed increases, the flow of the water becomes very stable and starts to maintain order. From this order I found a pattern and made it into a sound. And also, to visualize the flow of the water, it is blended with aluminum powder. We record the pattern of this flow with a CCD camera and change it into sounds.

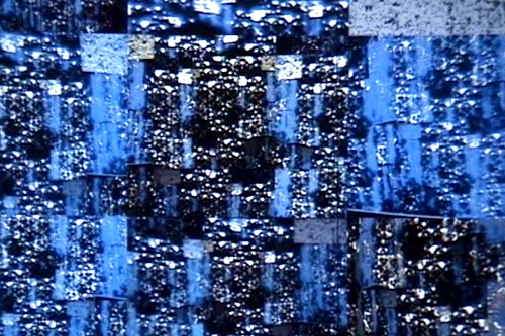

“Taylor Couette Flow”, Concept & Composition: Takashi Ikegami, Keiichiro Shibuya (2007)

Please explain how you can change something into a sound. What does this mean?

The sound that you hear coming out of the speaker is ultimately only the oscillation of the system, whether that sound is Mozart or Beethoven or some elementary school kid scraping away on a violin. Sad, but true. That is, whether it is the same single sheet of music being played by on the violin or piano; whether the performer is good or bad, it is the various kinds of mistakes, such as how good or bad the performance is or the tonal differences due to the equipment, that are how the Taylor Couette operates; it tries to distinguish the different of sounds by installing a system directly inside the systems. You might wonder why just flowing water would change the sound in any way, but it does: the patterned flow of the water creates a particular kind of turbulence and that also has a pattern. We scan the process on a CCD camera multiple times during the installation and then throw these into different algorithms. These create a noise that is not a chaotic white noise. That is how we create sound.

“filmachine”, Concept & Composition: Takashi Ikegami, Keiichiro Shibuya (2006)

But somehow this ‘natural phenomenon’ feels like it is art…

That was exactly what I was trying to do with Shibuya. I try to be right in the middle of process and expression, that is both a phenomenon and art. It’s not uncommon for art to be positioned as if it were lined up like stationery goods, standing in front of me, and it becomes ‘art’. That is not my approach; I like to think about the mechanism that ‘makes’ art. For example, there is a mathematical theory connected with the Taylor Couette called “the road from Torus to Chaos.” In my installation you can actually experience that theory with your body and eyes – how the process occurs; what changes take place — instead of trying to understand it by reading and writing about it. To be able to experience the fun and complexity is great.

That experience would be different from trying to figure things out in your head…

You use your body and experience the art so there is a lot of information coming in. Just generally speaking, there are so many things that you have to first try to experience by yourself to actually know about them, aren’t there? Art is not something that always has a meaning to it from the first, not even for us: artists who creates the piece doesn’t know what it is going to be until experiencing it themselves; the answers always comes later on. Also personally I always feel funny when I think of nature — it’s too much for me. That’s why I try to understand of nature by using something artificial. Instead of using something natural, I like to think of nature through something outside nature.

*One of the main areas of Ikegami’s research is what he defines as “Massive Data Flow,” which is about the massive amount of information people handle in their daily life. Not only their real lives but also the world of media that they so easily access, such as the internet, which carries much more information by far than people’s brains are capable of holding.

“filmachine”, Concept & Composition: Takashi Ikegami, Keiichiro Shibuya (2006)

The view of the world that was created by the Taylor-Cuette Flow had a sci-fi artificiality about it that I liked a lot!

Thank you, but I didn’t mean to do that! What I create is something just like a microscope. Or like an amplifier, I may say. I don’t try to make up fiction but the supernatural world that is created from these systems reflects the real world more than an actual real object. Just like people read novels because the story is closer to real life, not because it is fiction.

“filmachine”, Concept & Composition: Takashi Ikegami, Keiichiro Shibuya (2006)

Do your creations contain some kind a story or allegory?

No, maybe not. I just try to make something happen. In my research field of complex system science, storytelling is important but instead, what I like better is having many types of understanding or reaction. Take oil painting: in concrete terms, it’s not about what is being painted. For example, I don’t think Jackson Pollock is trying to make paintings with some kind of meaning. Of course, in the process of creation, there is some point at which metaphors somehow slip in, but I think there is nothing wrong with having some art that doesn’t actually mean anything, created between consciousness and unconsciousness. Many people try to label their works, but many of it is impossible to label in a single word. For me, questions like, “Are you a scientist or an artist?” or “Since you teach at school, when did you start art?” are meaningless. “I’m doing something I like,” is all I can say.

Recently, there has been an increase in the number of exhibitions about the ambiguity of the border between media art and contemporary art. To add to what you said about Pollock, do you think media art goes beyond the limitations or rules of art, like Pollock?

I don’t think there is much difference between media art and a visual art form, like drawing. I feel like they share common ground. In fact, there is a difference in terms of the tools that are used, but fundamentally, it all comes down to who the artist is. As everyone knows, a beautiful drawing is always more interesting than a “high-definition pixel image of something,” but the important thing is to think about why the drawings draw people too them.

On the other hand, there are things media art can do that are impossible in painting…

I think that when it is ‘possible to do anything’ that is the same as not being able to do anything. There always should be some kind of restriction in art. It has to be different from other things, or special. When it becomes something everyone can use, then it is no longer art. It’s the same with science. In this project called the SWARM Project in Santa Fe lab, there was a program that could make whatever we could simulate, clone or you name it. But after all, no one used it because the program was way too complicated.

To be honest, when I first saw media art about 10 years ago, I thought it was so boring — it just reminded me of sales demonstration by machinery companies. SIGGRAPH Asia (an computer graphics/intergraphic engineering exhibition) gave me the same feeling, too. Rather than that kind of thing, the work of such artists as James Turrell or Anish Kapoor or Joseph Beuys was much more interesting then! But now, 10 years later, media art is definitely more interesting. Something Kapoor was trying to do was to put somewhere in the computer to look for and then think out a new pattern for art; it was fun to see and try. But for me personally, I want to go bit further, so I am always thinking of the inner system that creates attractive art. I think that is because art is not my field, but if I want to do art, that is the only kind of approach I can take.

It is very surprising you don’t differentiate between art and science.

Many people tries to divide them. I also sometimes do for practical reasons. My friend Kenichiro Mogi told me, “An artist is a wild animal; a researcher is a wild animal trainer,” How you could possibly make them live together?” But actually he does the same thing, and da Vinci is a good example of this.

Does working in both fields affects each of them?

It has good and bad effects because the level of ‘precision’ that has to be maintained in science and art is very different. For example, in science if you read an essay by an outsider of the field, you recognize this immediately. Whether this is good or bad I don’t know, but fields or communities maintain and improve the precision of things. It is an important part of some kind of communities and is part of cultural evolution. So in that sense, you can’t be in the same ballpark without the same degree of precision in terms of knowledge. As for me, to sharpen my precision in art to raise it to another level was a very tough thing to do.

How could raise your level of ‘precision’?

Well, it is something you can’t see with your eyes, so you just have to visit museums, listen to lots of music, or, if it’s science, read a lot of essays, or those kinds of things. After repeating these things, eventually you kind of start to get it bit by bit. Of course, a kind of sudden meaning is a special to art, so people thinks art is a different thing from quality, but I don’t.

Seiko Mikami “Desire of Codes”, Installation commission by YCAM, Related work “MTM [Mind Time Machine]”, Concept & Direction: Takashi Ikegami (2010)

When an artist attempts to use an element from science, it tends to be something to do with the visual, with appearances…

Art that just uses the visual or the feeling of science is pointless. Science art is not about just using some scientific program or words that a scientist utters. I don’t like that approach; that’s why I never depend on atmosphere or feeling in my creations – although, when I did Desire of Codes, a show with Haruko Mikami, it changed my way of thinking a little. When it’s something really special, even starting out with just an atmosphere or a feeling for an idea, it is going to be tremendous, beyond a particular field or specialty.

Seiko Mikami “Desire of Codes”, Installation commission by YCAM, Related work “MTM [Mind Time Machine]”, Concept & Direction: Takashi Ikegami (2010)

You’ve also collaborated with the photographer, Kenshu Shintsubo on Rugged Timescape.

That was something that came out of a conversation with Shitsubo about the “lack of time” in photography. We made a program to scan a photograph and slip time into it, and tried to visualize the existence of personal time experience in daily life, by expanding it and cutting it up. However, this would not have happened without Shitsubo’s unique photographs and, first of all, the reason the corroboration happened was because I think Shitsubo’s creative is very interesting. The programme used in the installation was inspired by a theory of Vladimir Arnold, a well-known Russian mathematician. The programme itself has the simplicity of a problem students tackle for practice. It is something everyone in the field of dynamics knows, but generally speaking, most people do not know it. I don’t try hard to attract people to science, but using a mathematical theory as an idea and coming up with an interesting art creation is something I wouldn’t mind contributing to the science scene.

“Rugged TimeScape”, Kenshu Shintsubo + Takashi Ikegami (2010)

However, this would not have happened without Shitsubo’s unique photographs and, first of all, the reason the corroboration happened was because I think Shitsubo’s creative is very interesting.

“Rugged TimeScape”, Kenshu Shintsubo + Takashi Ikegami (2010)

The programme used in the installation was inspired by a theory of Vladimir Arnold, a well-known Russian mathematician. The programme itself has the simplicity of a problem students tackle for practice. It is something everyone in the field of dynamics knows, but generally speaking, most people do not know it. I don’t try hard to attract people to science, but using a mathematical theory as an idea and coming up with an interesting art creation is something I wouldn’t mind contributing to the science scene.

You’ve also joined some internet-based projects — tell us about internet art and its potential.

In my opinion, to focus on “time” may be the key to making art you have never seen before. In February, I created SoundBookShelf, a public art project, at the Aoyama Book Center. For this project I used a censor that measures humidity and temperature and set it up at the bookshop. Anyway, as part of the art show, I had a chance to have a conversation with Dr Michitaka Hirose, who researches and specializes in virtual reality. During this talk, we spoke about the way people have there own “right now” because of the internet. For example, on internet pass is very easy to access, as far as you want to. Also just think of Twitter: nowadays even the future is predictable at some point. And the past and the future that people search around becomes their feedback for their own “right now,” compared to years ago when it used to be that a personal opinion for “now” was totally controlled by social or public opinion for “now.” In the past few years, personal opinions in the internet world have become much bigger. It is hard to tell which is better for creation, but the circumstances have changed, for sure.

But the problem of this “now” is, it’s huge but it’s not rich, and I think this is the point people have to improve. Just like when people talks about how rich the days were before the internet did not exist, people notice exactly what they are doing. This shows the problem with accessibility to data: it may lose the richness of the “pure richness” of the information. Just like the Kurt Vonnegut story, The Sirens of Titan*. ability to go back and forward in time So next I want to create a technology that contributes to research on how accessibility to the past and future causes fluctuations in the human mind. Although sometimes it works out somehow, a superficial “good idea” doesn’t interest me, especially in science art. If technology is necessary for some sort of creation or art, I think there must be some kind of aim or purpose to it.

*In Vonnegut’s novel, the Tralfamadore planet residents are unable to understand the sadness of death

Do you think you will continue creating art in collaboration with others?

It’s hard to say. I wonder how many people plan what they are going to do. Perhaps for me, I don’t plan things very much; even though there are certain directions I am interested in, I enjoy things that do not always go like they should. When you plan too much, you think you failed when it’s not exactly what you expected, even when it is far better then you expected. And I also like trouble shooting for unexpected errors, too. In short, plans never work, isn’t that life?

I think so, too!

Especially when people ask me to do things, first it’s like, “how do I do this?” Things you want to do are usually controlled by time, budget, and whom you could be working with at the time. Given these limitations, while thinking about how you could make something happen, in the process you want to pick up as many meaningful side effects as possible. That makes the project something special. For example the side effect for building and shooting a rocket is the amazing view of it. At the start, it’s, “Let’s build a rocket!” but after its done, “What did you see?” becomes much more meaningful for the project. I always prioritize the latter, but on the other hand, it is almost impossible to predict what is going to happen. Fortunately, so far, I’ve never experienced a situation where there weren’t any side effects and I thought, “I have nothing I want to do.”

That’s amazing. I suppose it because you concentrate on what you have to do. Were you like that since as a student?

I don’t think so, but student life is a time that opens up a lot of different directions to take. In my case, it was my visit to Paris in 1998, where I met many artists, like Gabriel Orozco and Carsten Nicolai. Orozco is a Mexican artist who was not known at all then, but getting ready for his first show in Paris. We had a good time going out together. Now he’s done exhibitions at MoMA and the Tate Modern and he is busy. Meeting all those artists was very meaningful for me.

So that was the first encounter with art.

Actually, at that time I still wasn’t thinking about creating any art. But in 2004 I met Keiichiro [Shibuya] and we did a show together at ICC together in 2005. That was the first show for me. The performance and talk we did was a lot of fun for us. We called it The third term: Non-Fourier Formula and the beyond. We made five songs, and while Shibuya performed them, I explained how the ‘third-term music’ was made. I still feel that was an unexpected performance for everyone in the audience! It was a bit crazy in a way but it was really fun. I don’t think that would happen again. But then, I noticed so many differences between the performance and talk and science at a international scientific conference, where most of the audience knows what they are are going to see and even the presenter knows what questions will be asked. But at this art show, everything was pretty much unexpected. For this reason, there was a lot of pressure but as an experience it was something very special. I would not have known about something like this if I was just being a scientist my whole life, so I was happy to do it.

As they get older, scientists tend to get more closed, but it should be the opposite. It shouldn’t be just about refining the quality and purity of your life and then signing your name at the end – done! I don’t want to complete anything because it not fun after you finish things.

Having crossed over in so many fields, do you feel your personal view is unique?

When I started out thinking about the dynamics of evolution, I began to think about the origin of life. My next thought was to create artificial intelligence. But after that, I started to think that if I create a life, as a side effect, the intellect would come with it. So I think life comes before intelligence. In other words, intelligence evolves only from life. I have a mindset of thinking that way when I make art; I always try to create a metaphor of life and evolve it into art.

Have you been influenced by other art or literature?

When I was in high school, I read Kenji Miyazawa’s “Spring and Ashura,” which is still part of my motivation for research. Especially the opening poem expresses his philosophical point of view about artificial intelligence or robots. Although I don’t think he actually meant to write from this stance, for a scientist specializing in the field, it seems like all human emotion is just an illusion and every action is just a electrical signal, the same as a robot.

The basic rule for a scientist is not to believe in mystery, but in a way a scientist keeps on believing in illusion or magic or mysterious things. Although we keep on clearing them up. Even if one day, science explains all the riddles of DNA or neurons, the question of “what is life” or “what is consciousness” will be never solved. Instead of trying to find the answers to impossible questions, science is more about thinking in the gap between the solvable and the unsolvable parts. The poem explains it very well.

Text: Yu Miyakoshi

Translation: Andry Adolphe