EUGENIA LIM

PEOPLEText: Joanna Kaweckia

Rarely will you find someone as intriguing as Melbourne-based cross-disciplinary artist, director and editor, Eugenia Lim. Seldom is anyone able to execute this combination so well!

Passionate about unique work and original thinking, her influence is shaped by those around her and an honest reflection on her past.

Eugenia holds a great abundance of creative intelligence, expressed in a humble dedication to communicating extraordinary works and projects to the worldwide community through her online publication Assemble Papers. Additionally, as director of emerging Australian video art festival Channels, she bridges genuine connectivity and talent in curation.

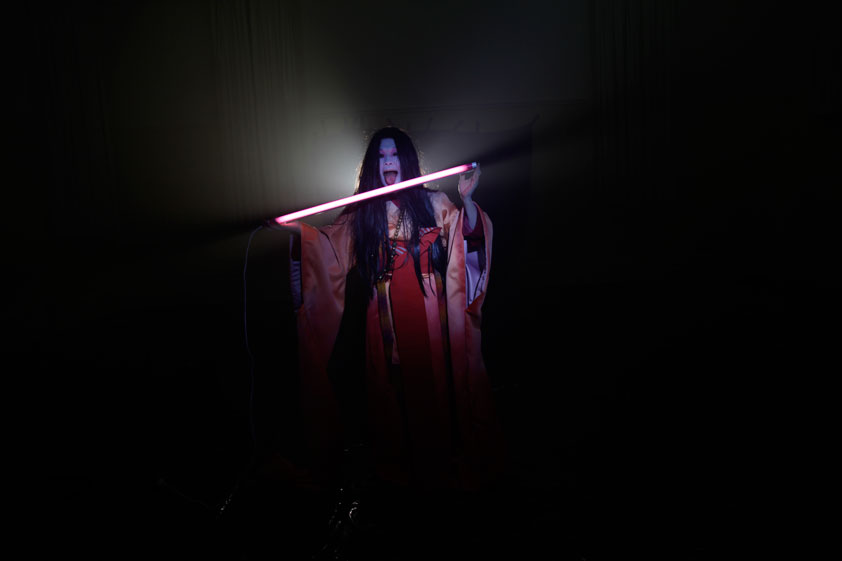

Forward-thinking in her practice of performance art, Eugenia tends to steer from the expected and encourages unique and progressive thinking through mediums of video, photo-media and installation. Such was a past performance entitled Stay Home Sakoku: The Hikikomori Project (2012), where Eugenia retreated from physical society for 7 days in a 5 x 5 metre gallery space, dependent on the generosity of strangers and the public on food and survival

A true visionary and fascinating individual, Eugenia is truly unlike no other.

© Quino Holland

Eugenia, please tell us a bit about growing up in Australia. How did this influence your passion for art?

I come from a family of doctors and over-achievers (it’s the Chinese-Singaporean thing). My parents moved to Australia about a decade before I was even a thought, moved around a bit, then settled in Melbourne where I’ve lived since. I’ve always felt at home here, but race and nationality are also never far away from my thinking and continue to be explored in my work.

I’m the youngest of three girls and I was a teenage rapscallion. I think my love of art and alternative forms of expression really grew out of this adolescent phase, trying to rebel, to create and find my own voice within a supportive but strict family and in quite an ‘anglo’ suburb and school. I was definitely angsty! I think I really found art via music and then writing and poetry. I was obsessed with local indie and punk music and grunge and I worked at KFC for around $50 a week (which meant I could buy 2 CDs). I remember dropping off a CV at Target dressed in a (pretty unoriginal) Nirvana t-shirt and angora cardigan like Kurt Cobain. During this “grunge Euge” period, I also started a fanzine with my childhood best friend Amy and we’d interview all the bands we had crushes on. Halcyon days. So I began writing and taking pictures and I thought I’d be a journalist or a graphic designer until I figured out that I don’t really like taking orders and I find the gaps (rather than the facts) in language, thinking and appearances, more interesting.

© Eugenia Lim

Indeed! And this is supported by your fascinating background, studying at Rhode Island and returning back to Australia to continue your practice…

Having lived all my life in Melbourne, I needed to experience living and making work in another context, to expand my field of vision. Somehow, instead of going to Germany or Japan, I ended up in another English-speaking country! I didn’t know much about Rhode Island School of Design but figured it couldn’t be too terrible and the fact that it was so close to New York was a real lure for me. When I got to New York and was staying with some friends, they mentioned it was one of the best art schools in the states (bonus!). It was a really important and productive time for me, living on my own terms, feeling foreign and out of place, but reveling in that point of difference. This was when I first started experimenting with performance on camera. As an exchange student, no one in class knew me; all they had to judge me on was my video and photographic work and of course, my appearance. At first this was terrifying, then in time, I found this extremely liberating, the idea of creating and constructing my identity through images. The works and experiments I made in the US were really formative and I continue to see the impact of that time in my work.

© Eugenia Lim

What is it about performance art and communicating ideas and evoking emotion that intrigue you about the practice?

I continue to be drawn to performance on video, film and live contexts because it is so fleeting; it can never be the same again. Even when a work is one of utter endurance and lasts days, weeks, or in the case of one of my heroes, Tehching Hsieh, years, this performance happens in “the now” and can never be repeated in exactly the same way. There’s a real excitement and frisson about being part of this exchange of energy, as either an artist or an audience member. I get a similar feeling when I’m seeing a band or musician play a gig – and the conditions are right for magic! As an Australian artist, many of my first experiences of “performance art” were in art school, through documentation of early works on video; and as a video maker, performance and video have become very intertwined for me. As a female artist, I find real power in the way women can both undermine stereotypes and reframe and enlarge their presence and identity through both performance and temporal practices. Art that gives me goosebumps is what I want to experience, and this is also what I’m working towards evoking in the viewer through my own work.

© Eugenia Lim

Do you have a particular influence or someone that inspires you?

Too many to mention, but I must list a few! I adore the work of Agnes Varda, especially her documentary/film essay The Gleaners and I. The way Agnes infuses her work with humour, intimacy and poetry is so inspiring. She is brave enough to video the aging process: her wrinkled hands, her greying hair and the passing of time and to also to make it interesting and meaningful for us. Sophie Calle is a hero too (what’s with these Frenchies?), her recklessness and bravery in fusing art and life I find really inspiring. RIP Chris Marker, I will always be intrigued and moved by his films Sans Soleil and La Jetee. Closer to home, young performers Atlanta Eke and Justin Shoulder are really interesting. I saw them both perform last year and was gobsmacked.

© Eugenia Lim

This year sees the first year of the inaugural Channels Video Art festival. What do you aim to create from the event? (More understanding for the medium?, etc)

Channels is an artist-led festival that aims to present video practice in its many “mutant” forms. The idea for the festival really grew out our desire to address the way video is created and perceived in the 21st century: on the one hand, video is one of the most ubiquitous and disposable of mediums (from YouTube to Facetime) and on the other, even though it is not necessarily object-based or easily collectable, it is now becoming the sought-after medium of choice at art biennales and in the “international art” world. Video is still a newish medium, but as curator and art historian Daniel Palmer writes, it’s one “without a history”, as each new generation rediscovers it and coopts it through advances in technology and shifts in culture. As makers and viewers, we want to present a program of screenings, talks, performances and installations that hints at the breadth and depth of contemporary video practice. We want to highlight outstanding and diverse Australian practitioners through an international festival that links our local artists to a global audience. Working collaboratively, curating, facilitating and nurturing other artists has been a part of my practice for almost 10 years and it continues to give me great fulfillment – it creates the kind of artistic community I want to be a part of. Channels is simply an extension of that invitation and I’m excited about it as it’s the most visible invitation to engage I’ve co-initiated yet. The festival is for artists, makers, thinkers and curious members of the wider public to explore, be provoked and ultimately be entertained.

© Eugenia Lim

What do you particularly admire about the art and architecture community in Melbourne, and Australia?

I admire the can-do attitude here in Melbourne. In spite of being one of the most expensive cities in the world, which means that almost every artist, designer, architect, writer and creative person I know, has to wear many hats and work multiple jobs to be able to support their creative practice; artists still find a way and to make work, publish books and magazines, curate shows, design temporary structures and ephemeral events. There’s a lot of cross-pollination, people collaborating on projects and I think this will continue. There are many niches and communities within communities here in Melbourne – while this can sometimes be overwhelming and feel like everyone is an artist – it means you’ll either eventually find a community you feel part of, or you’ll initiate your own. The myth of the heroic artist or architect with a singular focus is not so relevant for me and most of the people I admire. And in terms of the art, architecture and design stuff here, I similarly admire the stuff that is hard to define, that blurs and smudges the edges: like Joseph L. Griffiths “improvised architectures” in a site like the Docklands or the recent Action/Response series of site-specific works that encompassed dance, performance, architecture, sound and visual art during Dance Massive.

© Eugenia Lim

What was the latest thing you saw or read that took your attention?

A film I saw last week called No (directed by Pablo Larrain and starring Gael Garcia Bernal). It was set in the lead up to the 1988 referendum in Chile, in which the opposition to the Pinochet dictatorship was given 15 minutes of network TV air time each day to make their case for a “No” campaign (to convince voters not to vote for Pinochet). Told the story of a young advertising guru (Bernal) who took an optimistic and media-savvy approach to overthrowing a dictatorship, showing images of hope and humour, rather than the violence and sorrow that had occurred for 15 years under Pinochet. While it is a contemporary film, it was shot on video – from what I can tell, the same technology that was available in the 80s – and it looks warped and washed out, but the colours, the closeness and the vividness are so beautiful to me. It was a really strong example of when stylistic choices really match the subject matter.

Text: Joanna Kaweckia