“WOMENS’S ART” EXHIBITION

Is art made by women different than the one made by men? An interesting question that the State Tretyakov Gallery examines in their recent exhibition. In the building dedicated to modern art on the Krymskij Val, overlooking Moskva River just opposite Gorkij Park, the current temporary exhibition takes a stroll through the centuries, focussing on women artists. It is actually the first attempt to introduce genuine women’s art from as far back as the 1400’s to today. The exhibits cover a variety of traditional and modern mediums ranging from painting, graphics, decorative arts and installations. It thus has historical as well as contemporary character, looking at the specific development that women artists took and still face today.

Coming up the vast staircase, passing by the fabulous model for the Monument for the Third International (1919) by Vladimir Tatline (1885-1953), we turn to the left to the Temporary Exhibition hall. The Tretyakov’s permanent collection one floor higher is worth a visit itself: It houses many icons of modern art, the most famous of course being the Black Square (1915) by Kasimir Malevitch (1878-1935), and as it aims to encompass the whole of the Russian art of the 20th century, for the first time not distinguishing any more between pre- and post-revolutionary art, it creates an artistic continuum free of ideological barriers.

Plunging into the deep red mouth that creates the entrance to the exhibition, we enter the 15th century. In the ancient traditions of orthodox icon painting, the colour red signifies the suffering of human nature, martyrdom as well as blood and life. At the same time, red has always been the colour of the kings, and all these meanings can be found in the history of women artists.The exhibits start with magnificently embroidered clerical attire, normally in the collection of the Kremlin museums, dating back from the Middle Ages. In these days the work of women was mainly used to decorate the luxurious robing of church ministers. Using only exquisite materials and a rich image programs, these early examples are of a high value and unique importance.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Princess Ana Gruzinsky Galitzine, 1797, Oil on canvas, 135.9 × 100.3 cm

From the old part of Tretyakov Gallery, to show the chronological development of the course history took, are the next exhibits. In the18th century, the times had become less rigid, and the idling aristocrats used their overabundance of time to try themselves in the fine arts. Especially the female members of the royal family show a perseverance to be noticed. Maria Fjodorovna (1759–1828), wife of Pavel I (1754-1801), and her daughters painted a number of still lives, mimicking Dutch ones, and finished some carvings that speak more of the wish to find a convenient pastime by means of art than of a real mastering of the subject. Then, since the second part of the 18th century, professionally trained artists enter the scene. Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842), daughter of a French Classicist painter, is one of the first examples of a renowned painter of portraits that even got commissions by members of the court of Alexander I. In the upcoming bourgeois age, more and more free private art schools emerged, and now the idling upper classes would not only distract themselves by reading French novels, but also by pouring their emotions into paintings.

Sofia Vassilyevna Sukhovo-Kobylina, Self-Portrait, 1847, Oil on cardboard, 37.9 × 27.9 cm

When Sukhovo-Kobylina was the first woman to graduate with honors from the Imperial Academy of Arts, Russia. With these successes, also the female self-esteem rose, as we can see from the change of subjects in women’s paintings: If in the beginning they portrayed themselves together with their children or surrounded by their everyday belongings, now free and self-confident self-portraits appear.

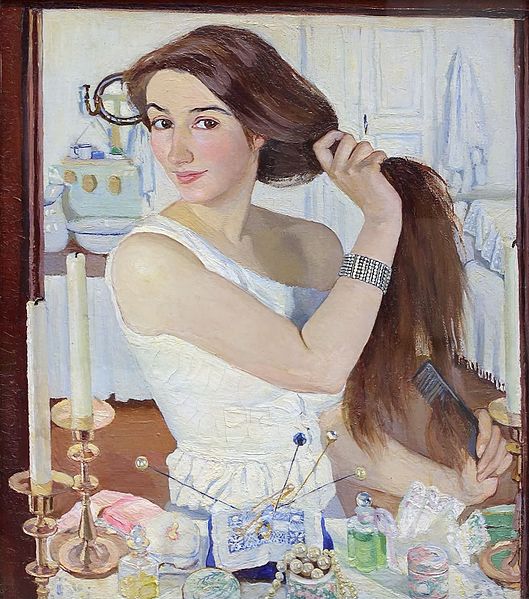

Zinaida Serebrjakova, At the Dressing-Table (Self-Portrait), 1909, Oil on canvas, 75 x 65 cm

When women finally could enter the state academies, they soon began to play important roles in the life of the art scene of their times. The Critical Realist Movement in the end of the 19th century, still a merely male new wave of artists from all over Russia, opposed to the soulless academic way of painting, found many followers also amongst the wives of then famous painters and writers who echoed their findings. Good examples are Olga Lagoda-Shishkina or Marina Fjodorova (1859-1934). At the turn of the century stands a remarkable figure: Zinaida Serebrjakova (1884-1967). In an extravagant interpretation of impressionist principles, but without becoming impressionistic as such, she revolutionised the stylistic momentum of neo-classicism. The world-famous painting “At the Dressing-Table (Self-Portrait)” (1909) shows hushed eroticism and self-admiration mingled with intellectuality and spontaneous perceptions.

Read more ...