PRISM OF THE REAL: MAKING ART IN JAPAN 1989–2010

HAPPENINGText: Alma Reyes

Three thematic perspectives are examined in the exhibition. In the first part, “The Past Is a Phantom,” artworks reflect the impact of wars and colonialism on the social, cultural, and individual mentality. The “Atom Suit Project” by Kenji Yanobe is considered “one of the great artistic leaps of the century.” Yanobe visited the Chernobyl disaster zone and risked exposure to radiation, but his Atom Suit creation, displayed inside a cubicle in the exhibition, functioned effectively as a “survival vehicle,” equipped with a radiation detection device, a metal panel display, and a loudspeaker for emergency alerts. The photograph “Atom Suit Project: Nursery School 1, Chernobyl” (1997) reveals a totally wrecked nursery ward haunted by broken toys and disheveled beddings. The artist sits numbly on the edge of a bed and appears drained with emotion. The work conveys a compelling message about perseverance and recovery and the ongoing nuclear disarmament controversies in world politics.

Kenji Yanobe, Atom Suit Project: Nursery School 1, Chernobyl, 1997, Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art © Kenji Yanobe, Courtesy of Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art

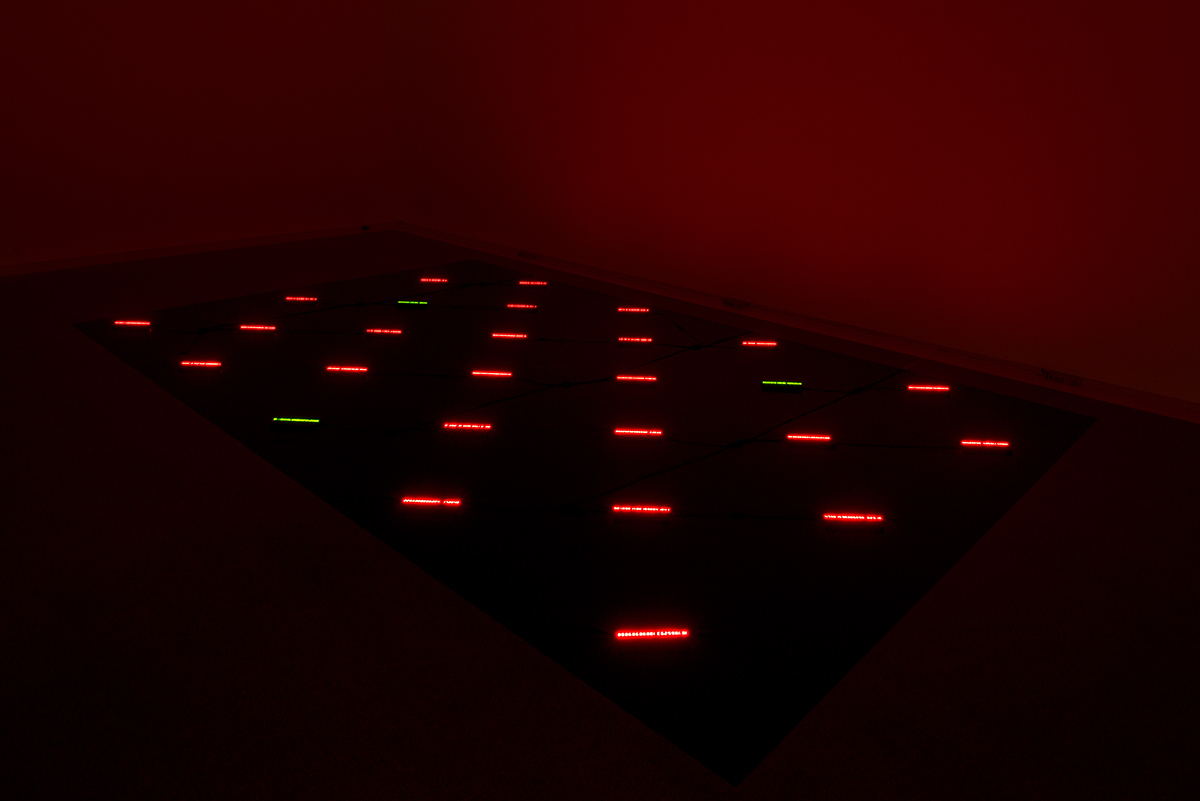

In the same section, “Slash” (1990), an LED platform installation in a dim room, lines up red and green digital counters in diagonal rows. The numbers 1 to 9 flash sporadically except for the number 0, which is replaced by complete darkness, indicating the end of life. Tatsuo Miyajima is well noted for his universal conceptualization of time and space and the tragedy of war. This work denotes the incessant human life cycle rotating around birth and death.

Tatsuo Miyajima, Slash, 1990, The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, Courtesy of The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

The theme “Self and Others” summarizes the prevalent contradictions in Japanese culture oscillating between traditional and modern and the search for personal identity. Gender and sexuality, and the clash between public and private spheres are also investigated.

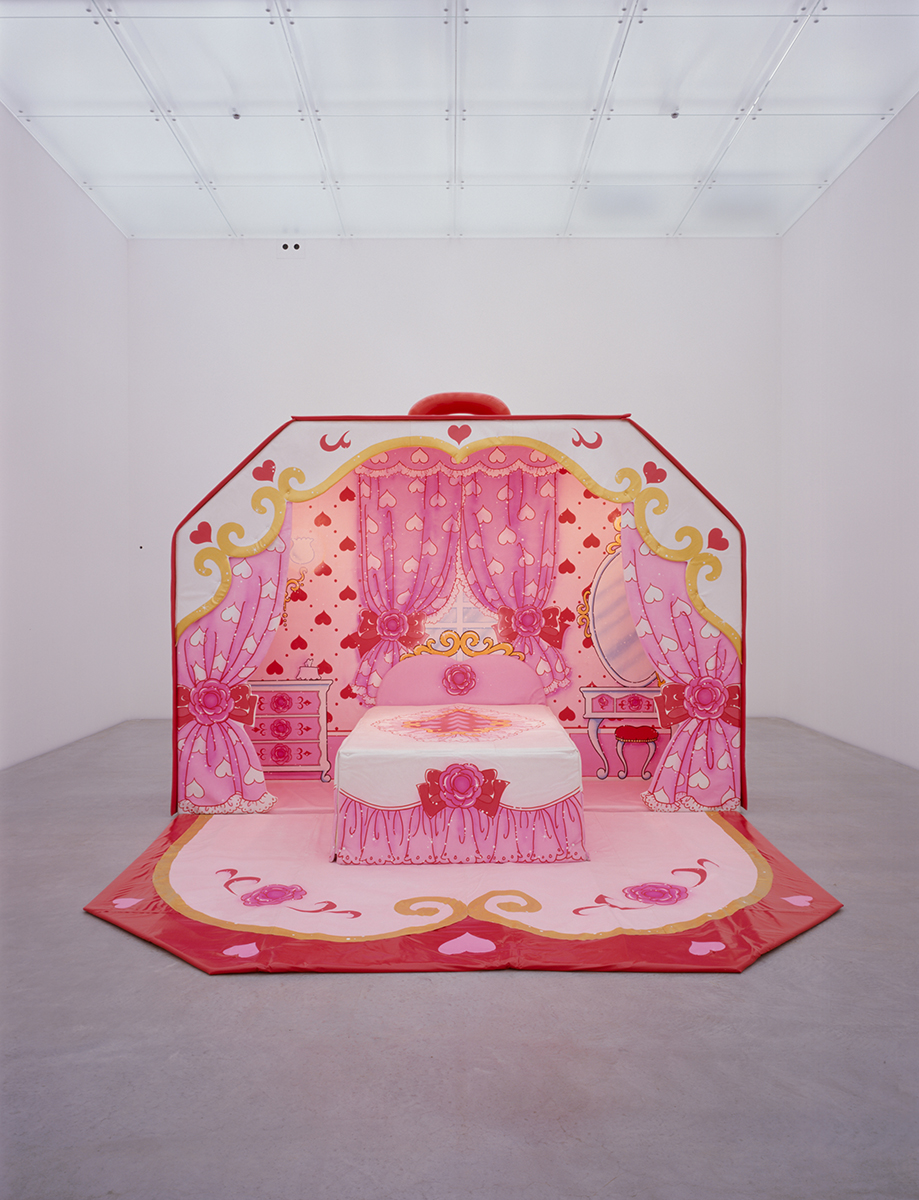

Minako Nishiyama, The PINKÚ House, 1991/2006, Collection of 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa © NISHIYAMA Minako, Photo: Mareo Suemasa, Courtesy: 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa

The sensationalized “kawaii” subculture in Japan burst vigorously from the seventies. Soon, by the nineties, it escalated beyond just a palpable trend. Cuteness, innocence, and childlike qualities found their permanent place in mainstream Japanese society. “The PINKÚ House” (1991/2006) by Minako Nishiyama, often identified with “girl culture” themes, perfectly epitomizes this social phenomenon. The life-sized, stage-like work depicts the house of the popular character Licca-chan, sought after by young Japanese girls. Dazzling pink shades splash profusely all over feminine motifs of hearts, roses, ribbons, and ruffles, drawing the invisible line between fantasy and reality. Further, the color pink in the Japanese sense can implicate sexual connotations, often found in adult-oriented advertising. The artist remarked, “Why do we think something is ‘cute’?…My current conclusion… is that it’s something basic in human DNA. I know I’m not the only one who likes blushing Japanese sweets or rosy sunsets… I just know there’s some common thread or shared core sensibility that connects us all.”

Read more ...